Blog/Polling

Bi_Focal #8: Heartlands, winners and elastic seats

I wrote a Times column about this recently. More thoughts on these questions (and more modelling to support) below.

Tories: a southern England party, actually

I was listening to a panel discussion earlier this year where a commentator repeated an increasingly common refrain that the Tory heartland had moved – and was now located firmly in the north of England amongst working-class, Leave-leaning voters. This struck me as odd. A lot of these seats were add-ons to a larger seam of political and electoral history which shows the Tory party as primarily southern. Looking through our modelling of vote share data over the past 30 years, it’s clear this idea suffers from recency bias. But the data reveals interesting things about UK politics and society.

The new collection of seats within the so-called Red Wall amount to no more than 45 seats (out of around 360 2019 Tory seats). We forget how southern-dominant the Tory party and the country at large is – 45% of Britain lives in southern England. I call this the “compass fallacy”. We think wrongly that 25% of the population sit in each of N/S/E/W.

The first thing that struck me about this heartland thesis was the suggestion that the vote share and seat gains that the Tories made happened disproportionately in the north of England. Looking back through the data, that is not true. The Tories got 2% more votes in the south since 1997 than in the north, despite the south yielding a much higher vote share in 1997 (40% vs 26%). They have also made more net gains since 1997 (using modelled boundaries) in the south than in the north.

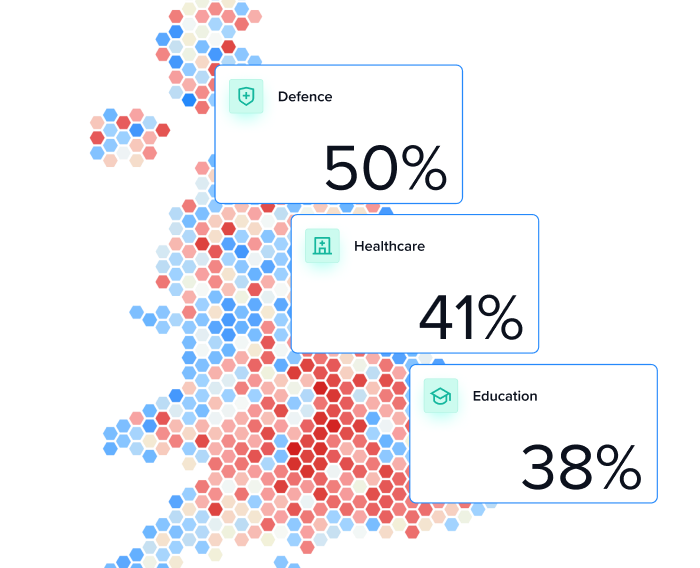

The second thing is that the thesis assumes that these northern gains were disproportionately Leave-leaning compared to gains in southern seats. This is also untrue. The relationship between the Leave vote and Conservative increase in support is substantially more linked in southern (government office) regions compared to northern regions (see chart below).

The third aspect of the thesis is that the gains made in the north were disproportionately from working-class areas and voters. Again, the data shows that all the gains in southern regions have come from more deprived areas, particularly if you look at the more rural areas – and they largely worked in lower-income jobs. But there is very little evidence of this in the north.

The stories that political movements tell about themselves matter. Recent events and shiny new votes can obscure political reality.

Our distorted view of PM winners and losers

Another erroneous thesis that has made the rounds over the past few years: former PM Boris Johnson single-handedly built the Tory vote machine that convincingly won the 2019 election. This is also incorrect. There is a sharp dislocation between the seat gains each Tory leader made from Howard to Johnson and the leaders that have put in the hard yards of increasing vote share.

Thinking about the 359 seats that the Tories won in England and Wales in 2019, May is responsible for the most vote share increases in individual seats across the six preceding electoral cycles. Specifically, she increased the vote share in 167 seats, more than any of her counterparts. Cameron, in his two election cycles, increased his vote count in 136 seats. Boris Johnson put on the greatest number of votes in only 29 seats of the 359 - that’s only 8% of the 2019 seat haul. I once estimated how May’s 2017 Conservative vote share would have stacked up against Jeremy Corbyn’s in 2019. This back-of-the-envelope maths suggests that roughly 70% of Tory gains at the 2019 election came from a collapse in Labour vote share.

Our recent political memory about which PMs were winners or not is heavily distorted by the personalities involved and the stories they tell about themselves. The data tells another story.

The "elasticity" thesis – why your biggest supporters aren't the most permanent

As a man of east Kent, it’s always fascinated me how local places have shifted back and forth so violently across political cycles. So I modelled general elections over time and adjusted for changing boundaries from 1992 to 2019 to dig deeper. It looks like the seats that absorbed the greatest Tory losses in the country in 1997 and subsequent gains were present across the Essex and Kent sides of the Thames estuary and coastal areas of Kent. Put another way: they had higher political elasticity – think of a rubber band that can twang back and forth. This is the defining feature of these areas.

In many ways, this is a re-cut of “Essex Man”. This shows the durability of Simon Heffer’s 1990 thesis that Essex Man was at the heart of the Thatcher coalition. This is highly unusual because these seats are now amongst the most Tory seats in the country – like Castle Point in Essex. This varies widely from Labour. None of Labour’s safest seats have been other than Labour in recent history.

One curious feature that I didn’t explore much in my Times column was the structural differences between the East and West coasts of England. Looking at the elasticity map, the concentration of highly elastic seats on the East coast versus the West is highly noticeable. This East/West division is present in the EU referendum. I remember modelling down the results at ward level: it showed an extraordinary band of hundreds of wards stretching hundreds of miles across purely Leave and purely Tory territory (from the Humber to Essex’s fractal coast). I’ve often wished for someone to explain the uniqueness of the East and what drives that. We can hypothesise: the very high levels of Englishness, its unique geography of marshland and lowlands, the history of the Blitz and the rebuilding of England, the placements of its hubs and spokes, and the inaccessibility of much of its coast all create a political alchemy – that has benefited right-wing politics over the past few decades.

I’m fascinated to see how far Labour can penetrate these areas – and whether the next election will prove again the elasticity of these seats in the East of England.

For further reading, I highly recommend Chris Clark and Tim Burrows on this topic and more.