Blog/In print

March of AI could prompt a white-collar revolt

The ninth anniversary of the Brexit referendum was an auspicious date for the Big Four accountancy firms to announce that they were slashing back graduate hiring. Their reason? Advances in artificial intelligence. There’s no obvious juxtaposition between the 2016 Leave vote, a very blue-collar revolution, and the decline of the graduate milk round. In a decade’s time, however, we may look back and reflect on another, very white-collar revolution that is about to take place. One that has the potential to upset politics just as much as the EU fissure.

David Goodhart, the writer who has extensively followed the inequity between blue and white-collar Britain, saw a decade ago that the odds were stacked against the former. Workers of the heart and hand — nurses, say, or construction workers — had been forgotten by the political establishment. Meanwhile, Britain had grown addicted to high migration and expanded higher education and deindustrialisation, creating a cocktail of compressed wages for blue-collar Britain.

These older, rural voters with less social capital, social mobility and less formal higher education shifted first to Nigel Farage, then to Boris Johnson and latterly back to Farage, each time registering their great unhappiness with the status quo.

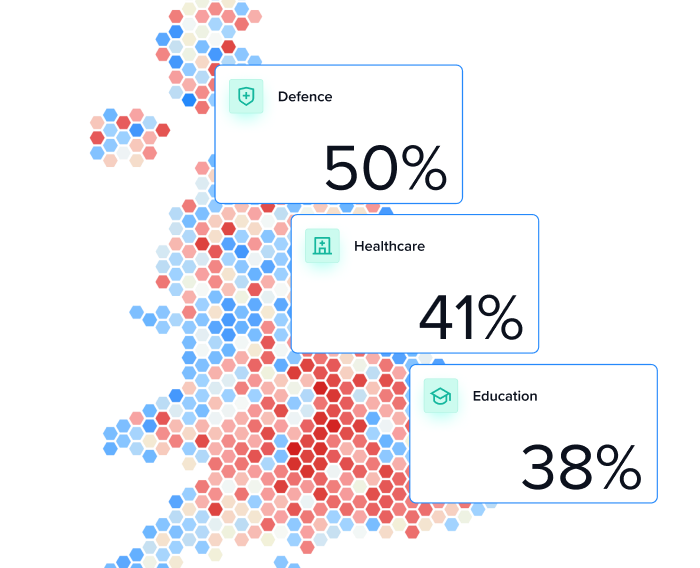

While Britain’s blue-collar revolt is still in full swing, AI might soon kick off a white-collar political revolution; a “collar flip” if you will. The new left behind may come from Highgate, not just Clacton. Our latest research at Focaldata, the polling company I work for, suggests that areas of Britain with a high concentration of high-income white-collar jobs are the most exposed to different AI technologies. Examine the exposure to AI by job type down to the level of the parliamentary constituency — using the government’s own job exposure analysis — and it is “comfortable Britain” that appears to be on course for an incredibly tough decade.

The top five constituencies at risk of job exposure to AI are Richmond Park, Hampstead & Highgate, Cities of London & Westminster, Battersea, and Wimbledon. Britain’s leafy, Remain-heavy, high-income London boroughs are about to face more trouble than they realise.

Management consultant and business analyst are the job occupations most vulnerable to automation; chartered and certified accountants the third highest. My profession, market research, sits in the top 10 per cent of most vulnerable jobs. The white-collar promise of stability and higher incomes may be imploding. The graduate earnings premium has been deeply eroded. Student debt, compounded by high interest rates and punitive marginal rates of taxation, is putting millions of graduates into penury.

Sky-high house price-to-income ratios in cities have weighed heavily on younger, white-collar Britain. Automation may be the final straw before white-collar Britain goes into full political and economic revolt. This significant portion of our society may be about to shrink rapidly, without much infrastructure to ameliorate the consequences.

There is also the other side of this “collar flip” to consider: what of blue-collar Britain? Might we be heading for a future in which we nudge our children towards the job stability of being a physiotherapist, a carpenter or a plumber, where once we spoke of becoming a doctor, a lawyer or an accountant? Automation analysis suggests that it is the skills of the body and hands that robots will come for last. Frank Herbert’s Dune hinted at this future in describing a world in which robots wrote poetry, but humans worked with their hands.

Meanwhile, look at the top ten constituencies where automation risk is lowest: eight are forecast as Reform holds or gains. Areas such as Boston, Great Grimsby, Stoke Central, Hull and Tipton all voted heavily for Leave and presently tilt strongly towards Farage. Broadly speaking, apart from areas that have a high ethnic minority population, the Reform vote tracks lower automation risk almost exactly.

When you look at the job occupation risk analysis, the link is even clearer. The government’s own analysis says that the top five safest jobs in the UK are roofer, construction worker, plasterer, steel erector and sports player. That’s a group of voters of which many are flirting with Reform. Our understanding of the left behind may need updating soon.

We don’t talk enough about secure blue-collar Britain, but it is a political subculture that Reform has tapped into deeply. Outside London and the southeast, the housing crisis is less existential than many make out. Young nongraduates unencumbered by student debt, and working in regular businesses that actually make money, rather than poorly paid London start-ups, are still described as blue collar.

The economist Thomas Piketty was alive to better terminology; his thesis broadly stated that the less money you had for the highest level of qualification – think the penniless postgrad — the more likely you would be to lean to the left. He called this group the “Brahmin left”. And the opposite group – people with high income and low levels of formal education — he called the “merchant right”. Automation, AI and large language models make the claims of the Brahmin left and the merchant right to be leaders of left and right respectively even stronger.

Automation is likely to take the loosening relationship between income and education levels and shatter it completely. Britain now has a heady mixture of metrics from which to measure privilege and grievance. Land, wealth, income, cultural power, education and job security no longer walk in lockstep with each other. You can be doing well on one axis but lacking on another. Academics call this “intersectionality” — broadly, it means that differing, ever-competing claims of lack of privilege have hamstrung the country, fuelled populism, increased division and not really made society better at all. Britain is a country where almost every voter feels they have lost out on something. We now live in Nietzsche’s world of multidimensional ressentiment.

If you want to understand why public polls show nearly three out of four Britons registering high levels of unhappiness with politics, it is because of a pervading sense, among almost everyone, that they are missing out. And perhaps the rise of AI may mean, for the first time, that almost everyone is.