Blog/Polling

Where does Britain stand on the future of defence spending?

As the official data partner of this year’s London Defence Conference, we recently surveyed the British public on themes including defence, policy and spending trade-offs, and the most convincing message carriers on these issues. Our CEO Justin Ibbett delivered a presentation at the conference on our findings. You can download the slides from Justin’s presentation here.

Summary

- We find there is tentative support for increasing defence spending in the abstract, but deeper analysis reveals a more cautious and complex landscape of public opinion when other policy areas come into focus.

- Voters tend not to view the current defence budget as poorly managed, but there is strong resistance to the possibility of future waste. This places a premium on demonstrating efficiency and clear value for money in any future proposals to expand the defence budget.

- When defence is tested alongside other policy areas, it emerges as a middling priority. Public concern is more sharply focused on issues like the NHS, education and pensions. Additionally, defence stands out as one of the most polarised policy domains we surveyed, making broad consensus difficult to achieve and potentially limiting the headroom for bold moves in spending policy or widespread shifts in opinion.

- Some areas within defence policy attract notable public support. Initiatives aimed at improving healthcare for military veterans and enhancing the UK’s cybersecurity capabilities are well-received, for example. However, those centred around procuring or producing new military equipment rank low on the public’s list of priorities. In an era where voters see the health service and other public services as lacking critical investment, arguments for boosting defence spending face an uphill battle.

- We also uncovered evidence of potential fatigue with sustained high levels of defence expenditure. Support for long-term elevated spending is limited, and there is opposition to targets such as raising defence spending to 3.5% of GDP.

Defence spending (in the abstract)

After a drubbing for his party in the local elections earlier this month, Keir Starmer gave his first public appearance at a defence contractor in Bedfordshire. Yet defence was not really on the agenda at the local elections – some MPs, councillors and other party figures instead blamed Labour’s losses on cuts to winter fuel payments and welfare spending reforms.

The competing policy priorities in the governing party between defence and welfare may come squarely into view in the coming months, with pressure on Labour from MPs to reverse spending cuts in other areas while the party leadership continues to pledge an increase in defence spending.

While the government may be drawing on internal polling which suggests increasing defence spending is popular, our research suggests it remains tentative. A plurality of voters (35%) favour increasing the defence budget to ‘strengthen military capabilities and our ability to respond to global threats, even if this may mean higher taxes or cutting other things like health and education’. In contrast, 21% support a reduction to redirect resources towards domestic priorities such as health, infrastructure or tax relief. Over two in five Brits either want defence spending to remain where it is or are unsure.

The overall national lean towards increased spending is largely driven by Conservative and Reform voters, around 45% of whom back higher defence spending. Among voters from other parties, views are more evenly divided, with Green voters the least likely to want the defence budget boosted.

Perceptions of how effectively the defence budget is spent are also comparatively positive. Among seven major policy departments, defence ranks second in perceived value for money among the public, with an average rating of 2.94 on a scale from 1 to 5, where 5 denotes excellent value for money and minimal waste, and 1 indicates poor value and significant waste. Only pensions scored higher (3.08), while defence was even rated more favourably than the NHS (2.69).

However, there are significant risks going forward for the government and other advocates of defence increases if a spending boost comes without a properly targeted plan. While the public typically views the defence budget as well spent, they also remain strongly averse to the idea that waste would be a necessary by-product of progress. Fewer than one in four respondents agreed that inefficiencies or failures can be justified even if they lead to innovation or strategic advantages. A majority of Brits reject the notion that the ‘price of progress’ includes tolerance for waste, emphasising the need for accountability and demonstrable results in future defence spend.

Defence spending (in practice)

It’s easy for politicians to pinpoint a specific policy that polls well in isolation as a vindication of their wider strategy, but this is where it’s crucial for researchers to use the tools at our disposal to determine the importance of a policy in context. Voters may agree that they want a whole shopping list of spending commitments from the government when those commitments are surveyed individually, but taken as a whole, voters may reject politicians who propose widespread increases in public spending when the hard realities of funding come into play.

Politics is often a game of priorities, so to better understand voters’ actual preferences across departments, we used a MaxDiff (Maximum Difference Scaling) exercise in our survey. This method asks people to repeatedly choose the most and least important options from small groups of items. It forces trade-offs, revealing not just what people want, but what they value most relative to other options.

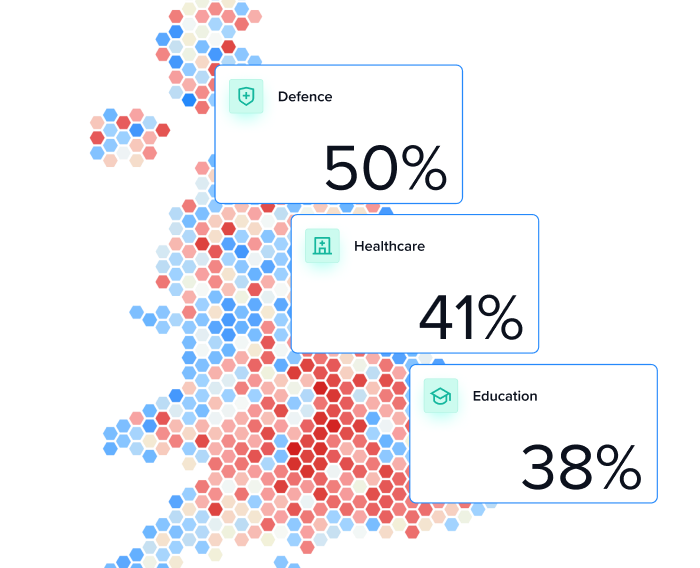

When it comes to actual public spending preferences across the piece, defence ranks as a middle-tier concern for voters, behind areas like the NHS, pensions and disability benefits. Out of 13 policy areas assessed, defence placed 8th in terms of public desire for increased funding. In addition, it also emerged as the most polarising issue in the set. Defence ranks third highest for the number of voters who want spending increased – yet simultaneously ranks fifth in terms of the number who want to see it cut. This sharp division suggests that any political consensus around defence issues going forward is likely to be particularly difficult to achieve outside of any immediate major threats to Britain’s security.

This polarisation on defence is also evident at the policy level. Among 30 specific policy proposals we tested, two defence-related policies ranked well in terms of public support (8th and 9th), but the others performed poorly, at 20th, 24th, 25th and 29th. The results suggest that public support for defence is highly contingent on the nature of the policy, with some policies likely to switch a lot of voters off.

In this test, all three NHS-related policies we tested emerged at the very top of the list, illustrating the dominant position of healthcare in the public’s mind and reinforcing the challenge facing Labour and others in making the case for greater defence spending at a time of high concern for struggling public services and a cost-of-living crisis.

It may well be the case that an increase to defence spending is a necessary and sensible response to the current state of global affairs, but the public has not yet been won around to this way of thinking.

Fatigue

The public is evenly split on whether elevated defence spend should be sustained over the long term. Forty-two percent of voters believe it is important to maintain higher levels of defence spending even if the national security threat diminishes in the coming years, arguing that long-term investment is key to deterring future risk. This group is matched by the 41% who think spending should return to previous levels if the security threat reduces.

A similar division exists when it comes to expectations around results. Again, forty-two percent say they would be less supportive of sustained high defence spending if they do not see clear outcomes or progress. Meanwhile, 41% take the opposing view – that national security requires consistent, long-term investment, even when the benefits are not immediately visible.

Within the broader public, around 20% fall into a more conditional category on defence spending: they support maintaining or increasing spending but expect it to be rolled back over time if security threats ease or if demonstrable results fail to materialise. We would call this group ‘at risk of fatigue’. This group does not appear to be concentrated in any particular demographic segment, suggesting fatigue may set in fairly uniformly and quickly if and when it does.

Swing voters

To get a view of where support for defence overall is strongest, and where opinion is perhaps more malleable, we conducted a segmentation analysis using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA can uncover patterns in how people think by grouping respondents based on shared attitudes. In this case, it allowed us to classify the electorate into seven groups based on their views on a whole tranche of questions: defence spending, responsiveness to arguments for or against it, attitudes towards the defence industry, and how they prioritise defence relative to other policy areas.

Group 1 is the segment we categorise as the most strongly pro-defence, consistently supportive across spending, policy and industry dimensions. At the other end of the spectrum, group 7 is the most anti-defence. The middle three groups (3–5) are the key ‘swing voters’ on defence. These individuals either hold mixed or uncertain views, making them a critical audience for shaping future defence narratives and building support or opposition on defence policy.

Labour voters and non-voters are disproportionately represented in these middle groups, suggesting that they are more likely to be persuadable or still forming opinions on defence issues (which no doubt will be shaped by actions of the government in the former case).

Age is the other key differentiator. Younger voters are significantly less likely to hold firm positions: over 60% of those in the youngest age group fall into the middle three segments, compared with only a quarter of voters aged 75 and over. In fact, across all age groups under 45, a majority fall into the ‘swing’ categories, indicating younger demographics will be pivotal to shaping the future of Britain’s defence policy in the next 12 months.

Data tables

Data tables for the survey can be accessed here.