Blog/Analysis

Bi_Focal #11: What Explains Our Politics?

In last week's Bi_Focal (click this link in case you missed it), we looked at the rise in polling numbers for Reform, and the degree to which this poses a challenge to the Conservative party support base. We also explored why people feel drawn to Reform - and why their supporters shouldn't be treated as merely disgruntled ex-Tories.

This week we cover two really interesting things. First is how when political parties campaign on social issues they can create super-majorities in a way that's much more difficult to do so when talking about economic issues. The second major thing we take a look at is a retro on that YouGov MRP and what we think this means for the next general election.

Social issues and economic ones present differently

One of the takeaways of Part I of last week's newsletter was that British society is pulled apart on two socio-political dimensions, with an economic left-right axis, and a social left-right axis. Political party supporters sit in different areas on this 2-dimensional space. Labour's tend to sit left-left on average, Tory's right-right, while Reform's supporters occupy the social right-economic left space -- "traditional socialists" whose position on social and economic issues is out of kilter with how the party projects itself.

More generally, the social dimension really drags our respondents apart in their views, while their take on economic issues is less dispersed. This tells us that on social issues Britain is deeply divided, with slightly hazier differences on economic ones.

We can see this also if we look at YouGov’s top issues tracker over the past decade, shown in the figure below. This suggests that economics have become much more salient for the public (we’ve covered this before in this Bi_Focal here). Social and economic issues therefore not only divide the public, but also occupy top of mind in different ways and at different times. What's going on is that, while the noise around Brexit crowded out economic issues for a time being, there’s a wider phenomenon at play: social and economic issues can crowd each other out – attention on key issues seems like a zero-sum game.

Figure 1: Britain's most important issues over time

This all seems odd: economic issues are top of mind but social issues are what really separates parties and their supporters.

We think what's going on is that social and economic issues operate in completely different ways in how they absorb public attention and divide public opinion. We talk about the Overton window; a term to describe the gradual shift of public attention and acceptance on issues. But it’s possible that on social issues (crime, immigration, national identity, trans debate etc.) the window moves around more violently than on economic issues. Social issues tend to provide a richer pool of ‘hop over issues’ and supermajorities for both sides. Social issues allow, say, a remain-voting Kensington lawyer to sing from the same hymn sheet as the right on wanting Shamima Begum locked up and passport confiscated along with 85% of the country, but nonetheless in the same poll argue that everyone should be treated equally - again with 80% of Britain.

Our hypothesis is that people are more flexible on social issues - but paradoxically they feel them more acutely and with a greater degree of political intensity. We might think of intensity as being negatively correlated to flexibility; (think of the phrase “strongly-held”) but what if you could be both more intense about your social views, more clear, but also more flexible? Economic issues are the opposite: they have low cognisance, not well understood, have high variation within partisan buckets but don’t move across the ideological divide.

To test this hypothesis, we plotted our survey respondents our 2-dimensional economic-social graph (see Part I for more info on how and why we did this). The general pattern, recall, is to divide respondents into quadrants by their latent preferences, with archetypes as in the figure below. This gives us a powerful lens to look at where people sit on more granular socio-economic questions.

Figure 2: Archetypes based on social and economic left-right axes in the data

Social issues split the public cleanly and show clear supermajorities

So what we can do is plot on these axes the average responses to particular agree-disagree social and economic questions we asked respondents. What we'll see is that the planes that separate those in or out of agreement are hugely different depending on what kind of issue we're talking about.

Starting with social issues, my favourite polling question - already referenced - in a UK context for its sheer force of strength is the Shamima Begum question. When you poll various versions of this case you found the most comprehensive expression of right-wing opinion in Britain. Only 4% of Britain think that people who commit terrorist acts with foreign passports should not have their concurrent British citizenship revoked. This polling question is where the Conservative option delves deep into Liberal country, where young, highly educated urban respondents would ban and remove British citizenship from the Begum’s of this world. If you’re reading this and think that’s problematic - you are part of one of the smallest and least representative portions of the UK electorate.

Reflecting on this polling, there’s a case to be made that the Labour party narrowly avoided total electoral apocalypse in 2019 – Corbyn liked to fight on issues that had trace elements of the Begum case, and had they been fighting on an issue similar to this as a proxy of voting intention Labour really could have been reduced to rubble.

Other issues - less salient - like the participation of trans women in sport, which show the same cross-cutting impulse and super-right majority. Or the strong dislocation between elites in being tough on crime – a driving issue of Blair’s 1997 campaign – and clear agreement among most of those we polled for tougher sentences.

Then we’ve got the left supermajority issues – expressions of the nation's deepest left wing impulses. Below we see a formulation of equality that works: the statement that “People from all backgrounds and cultures should be treated equally, and have access to equal opportunities”, supported by 80% of Britain, and only 5% disagreeing.

In contrast to these supermajority topics, other social issues show cleaner attitudinal lines that move flexibly and divide public opinion sharply: immigration, refugees and minority-discrimination in particular. These are polarising issues – and why they dominate the agenda, not necessarily salient in people’s everyday lives but creating a self-sorting mechanism among the electorate.

Economic issues are hazy, with no clear winners

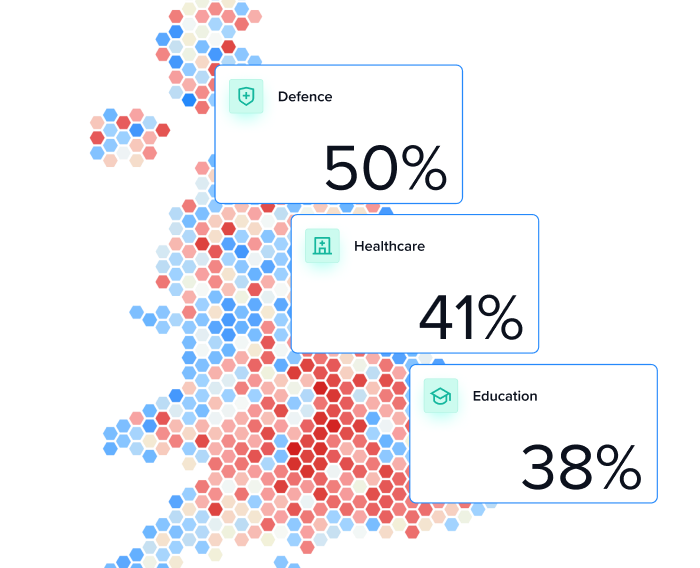

Social issues, in short, operate like a “cheat code”, hacking into latent divisions in the public in clean ways, with the potential to create right and left supermajorities. Economic issues operate completely differently; they don’t split opinion like social issues. There are left-wing super majorities on issues on which everyone agrees – NHS support and funding, and tackling the cost of living crisis. These are politically uncontested except at the fringe (at least for now). But unlike social issues, the divisions are totally different: there is no right wing, super-majority equivalent. Britain’s low tax, libertarian wing has completely left the public opinion pitch.

These figures echo our party attitude map from earlier: the social dimension stretches the public out, while the range on the economic dimension is narrower – people are drawn to the economic centre.

This has huge consequences to British politics: there are much fewer “victory levers” politicians can use on taxes and spending, only necessary hurdles that all parties have to overcome: protect the NHS, tackle cost of living and invest in public services.

In our current environment where public opinion leads policy direction – for both major parties – the sound and fury for tax cuts, abandoned £28bn spending plans, reimagining the role of the state, tackling the productivity crisis, the complete rewiring and re-tooling of our system … all will have to be done without any particularly strong polling case to do so for or against.

Economic issues seem much more subject to question framing. See the large majorities for lowering the tax burden on everyone, taxing the wealthy more while abolishing inheritance tax: strongly related economic issues which are stretched apart differently along the two axes.

What’s also striking is that the framing of welfare and benefits also matters: introducing a universal basic income and boosting benefits follows traditional economic dividing lines, but framed in terms of the welfare state is polarised along a Brexity axis.

A second feature of these hazy economic issues (hinted at in the above figures) is how some economic issues come to the party dressed up as economic, but are divided on a social issues axis: inheritance tax, taxing the wealthy and the size of the welfare state to name three. The latter is especially clear: agreement is determined exclusively by the social dimension, barely budging across the economic axis. And then, finally, we’re left with issues on which the public is united: against privatisation and for investing in the NHS.

Public opinion and public policy are connected on economic issues

What does Britain’s diffuse views on economics mean? Why should we care? We think it matters. For years Britain’s public opinion has been a useful tool by which the state has been enriched and enlarged when it is too small, and cut back when it is too big. Like some magic act of political-economic homeostasis. It’s hard to know the direction of causality but public spending as a % of GDP has tracked views on reducing the state/maintaining levels of public spending for thirty years. Covid - and perhaps the culture wars - seems to have broken that. We have a massively enlarged state, but for the first time we don’t have a concurrent rise in public opinion calling for reductions in state spending. This is almost certainly linked to worse outcomes for visible spend across the public sector but I think it really matters.

Figure 3: Govt spending on GDP vs public attitudes towards tax

Note: Missing years infilled. Source: British Social Attitudes Survey and Statista

Looking ahead to the General Elections

Economic and social issues not only drive wedges between party supporters but the public also treat them differently. In a context where economic issues are top of mind and less contested, this means that social, culture-war issues, will continue to provide the fodder for the embattled Tories and rising Reform to try win over more voters, while Labour try not to rock the boat.

Can the Tories do this successfully? Many are sceptical and predict a Labour landslide. In fact, I’ve not seen an MRP cause quite as much fuss as the YouGov MRP conducted recently, but like them we think the Conservative chances of a wipeout are being overestimated - and agree with pollsters like Peter Kellner. Digging into the YouGov numbers though a couple of really interesting things pop out.

- A very different distribution of votes - the margin Labour need to govern as a majority vs the Conservatives has moved from 12% in 2019 to around 5-7%; clearly more efficient

- Scotland’s vote is incredibly leveraged and so any ballpark estimates right now are a bit pointless

- If you apply average incumbent increases in vote shares to the polls today you get a similar picture to the YouGov model, or actually even more positive for the Conservatives

- Essays on the “death of a party” are usually a 3 year forward indicator that they are about to recover

- Swing back to previous incumbents is pretty large - the analyst Owen Winter has done some excellent work on that, and almost always happens - not because of events but probably because of esoteric question wording effects like prompted party polling being slightly out, Don’t Knows that look like Government supporters returning amongst other things.

While the rise of Reform therefore gives us reason to dig into how the public is currently positioned on core issues, we are (likely) still a long way off from an election: how economic and social issues fit into and the public discourse may yet be determined - expect an update on shifts in attitudes in due course!

Sample

Focaldata online polling of 2,746 respondents in Britain. Fieldwork was carried out between 21/12/2023 and 16/01/2024. Data is weighted by reported age, gender, education, ethnicity, region and 2019 General Election vote.

This blog comes out as a newsletter before we publish on our website. If you'd like to get ahead of the curve, why not subscribe and get the next one straight to your inbox. You can also follow Focaldata on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Feel free to check out our previous editions of Bi_Focal:

- Part I of this newsletter, on the Rise and Rise of Reform, released last week - link here

- Our MRP of the Voice referendum in Australia (we were one of the closest pollsters to the final vote tally) - link here

- A new theory of "elastic seats", a defining feature of pivotal areas with large variation in voter support over time - link here

- Stripping down how the British public see their leaders -- link here

- A deep dive into Scottish politics to see how much trouble the SNP were in when Yousaf started out -- link here

- Our (now year old) stress test of predictions about a Labour landslide -- still valid a year on, we think! -- link here

About Focaldata

We're on a mission to power the world’s understanding of what people think and do.

We research public opinion for data-driven organisations. With Focaldata, decision makers and researchers get the most rigorous data and analysis at 5x the speed — reducing the time to decision while delivering uncommonly actionable insights. We are a team of engineers, data scientists, product specialists and researchers building outstanding technology and next-generation services. Our services are global. We are non-political and non-ideological.

Find our more: www.focaldata.com

Sign up to receive the next issue of Bi_Focal

If you have any thoughts or feedback, please email me at james@focaldata.com.