Blog/In print

Farage is pushing Scotland to independence

This article originally appeared in The Times

Almost half a century ago, Tam Dalyell famously raised the imbalance between English MPs and their Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish counterparts. This so-called West Lothian question, named after his constituency, still illuminates British politics.

Now there is a new significance to this southern shore of the Firth of Forth. History likes a rhyme, so it was here of all places that Reform UK won their first elected Scottish councillor a few weeks ago. One of West Lothian’s nine wards, the towns of Whitburn & Blackburn, returned a former police officer, David McLennan, by 149 votes over the SNP.

Reform’s victory in a left-tinged ward is a strong signal of its growing strength in Scotland — and of future challenges for the Union.

Nigel Farage’s success in England is baked into public consciousness. Victory for the 2016 Leave campaign aside, his Ukip vehicle won 27 per cent of the vote at the 2014 European elections; his Brexit party increased that to 30.5 per cent at the next European elections in 2019, coming first in 267 of Britain’s 372 local authority areas.

That 2019 election map looks uncannily similar to today’s Westminster forecasts showing Reform with more than 300 Commons seats — and the SNP taking most of Scotland. It was a harbinger that Scottish nationalism tends to thrive when the harder-edged right does better in England.

What’s different today is Farage’s political success in Scotland. In 2015, Ukip was backed by one in eight voters across Britain but only one in 60 Scottish voters. In 2024, under the banner of Reform, this edged up to one in seven UK voters and about one in 14 north of the border. Recent polling from Ipsos Mori has Reform being backed by one in five voters in Scotland.

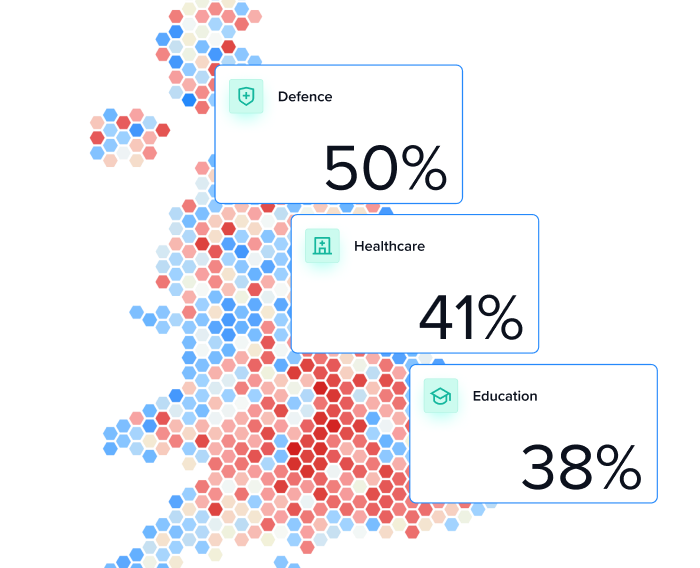

Based on modelling from my company Focaldata, a quarter of Farage’s biggest gains in parliamentary vote share over the past decade are in Scottish seats — high when you consider how few Westminster seats are Scottish. Projections for next year’s Holyrood elections show Reform has a real chance to become the official opposition. Equally clear is the gap between Reform and the SNP, with the latter 17 points ahead.

The good news for the SNP doesn’t end there. Support for Scottish independence is now polling at 52 per cent. More tellingly, Ipsos indicated one in six unionists would reconsider their support for the UK if a Farage-led Reform government was returned in London. If it was a Conservative government, only one in 25 unionists would have cause to rethink their support for the Union.

But if all these unionist waverers acted on their concerns over a Reform government, support for Scottish independence would edge up towards 60 per cent, something approaching endgame territory for the UK.

If we believe the current polls about Reform’s rise — and council by-elections like the recent West Lothian one suggest we should — we should also take seriously the evidence suggesting weakness in the Union. Britain’s gravely fragmented politics means winning parliamentary elections can be done with an enthusiastic coalition of just over a third of voters. Referendums, by contrast, with their static winning post of 50 per cent plus one, are won thanks to the apolitical or ideologically conflicted. It appears the idea of a Farage government is giving ideologically conflicted Scottish unionists pause for thought.

Unionism is not under threat just by dint of Reform’s rise. The past 11 years since the question was last posed to Scotland’s electorate have seen multiple seismic events (Brexit, the 2019 election, Covid and the Liz Truss budget) all of which have increased — temporarily — support for independence.

On top of that, our modelling at Focaldata indicates that when the right-wing parties — the Conservatives or Reform — do better across Britain, support for Scottish independence rises. For two parties that support the Union, this points to a dysfunctional relationship across the border.

Like a Tom Stoppard play within a play, Scottish and Westminster politics interact dynamically with each other while maintaining the fiction they are played out separately. Political shocks inflate support for independence from time to time, but it tends to evolve more in response to whether the right-wing vote south of the border grows or shrinks. The collapse of Labour’s nationwide sandcastle majority and the rise of Reform have led to the collective right-wing vote across the country rising by nearly ten points since the 2024 election.

Right-wing ascendancy at Westminster brings constitutional pressure in Scotland. I’ve long been convinced that the key to understanding constitutional politics north of the border at any given time is determining what is more important to left-wing unionists — their politics or their unionism. The data suggests that the possibility of a Reform UK government may mean some unionists prioritise their left-wing beliefs ahead of a desire to remain part of the UK.

Nationalism is also likely to ride high in Welsh elections next year. Plaid and Reform are vying for first place in the Senedd and Wales looks set to split on national identity, with Reform likely to do better among those who regard themselves as English and/or British and Plaid among communities which identify as Welsh. In Northern Ireland, Sinn Fein is still topping the opinion polls before the 2027 assembly elections. The next couple of years could see parties that wish to break up the Union in first place across Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland; a moment of peril for the Union.

Yet the great paradox of all of this is that widespread political dissatisfaction, and voter concerns over the economy, the health system and immigration, are similar across these islands. The same desire for change and a reboot is producing quite different outcomes across the home nations.

For unionists there is a chink of light. In Scotland, a third of Reform voters are pro-independence. Such voters — let’s call them Leave-Leave — are an underexplored and fascinating tribe in Scotland. And Farage has the opportunity to convince his own voter base, in Scotland and across the UK, of the merits of the Union. Even those who oppose Reform may wish him well with this challenge.