Blog/Polling

Has the time come for Proportional Representation?

Why now?

After bubbling away in policy circles since the AV referendum in 2011, the debate over electoral reform is likely to burst back into the mainstream in the coming years. There are a few major factors driving it there.

Last year’s general election delivered the most disproportionate result in modern British history, with Labour’s landslide majority built on barely a third of the vote. When two-thirds of voters do not get the government they voted for, the electoral system will rightly face a crisis of legitimacy.

Relatedly, the UK is now clearly in a five-plus-party system, with the largest ‘effective number of parties’ since World War II. Elections held during the Brexit period of 2016 to 2020 masked the long-term trend that the UK was heading towards an era of electoral fragmentation.

Since the election, voters have split even further, with five parties now regularly above 10% in the national opinion polls. The effect here is that seats under first-past-the-post can be won with barely a fifth of the vote, which is a big problem for both the voters and the elected representatives themselves, who may struggle to do their jobs effectively given their lack of electoral mandate. In May’s local elections, one winning Lib Dem candidate won with just 18.9% of the vote. Hardly a ringing endorsement of the candidate or the electoral system.

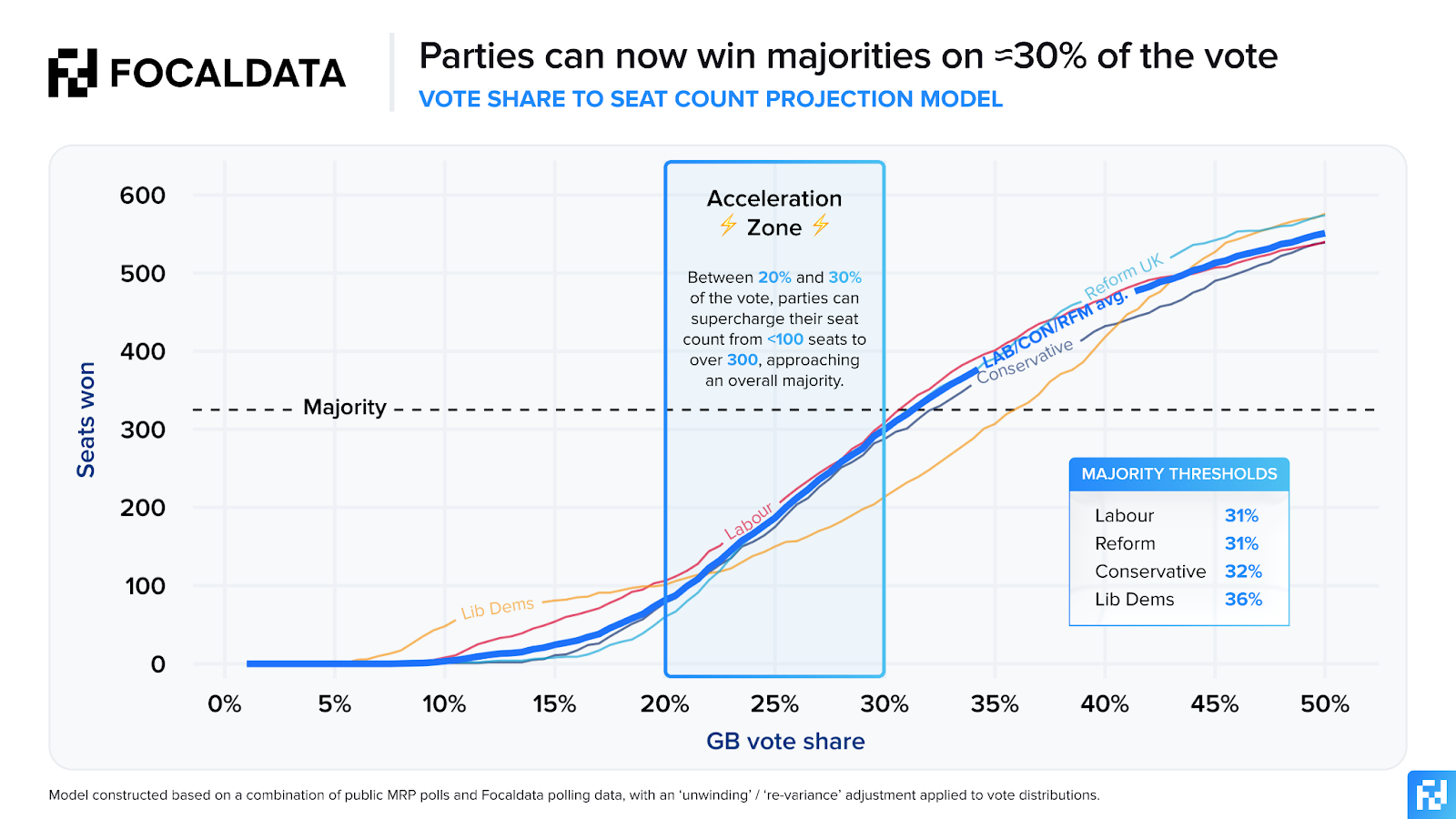

Looking ahead, Reform UK could theoretically end up winning a majority of seats at the next election with barely 30% of the vote. Of course, as the recent Caerphilly by-election showed, tactical voting and local dynamics could blunt that somewhat, but this fact still undermines how distorted outcomes are becoming under first-past-the-post.

Meanwhile, the issue is already bubbling up in Westminster. A recent (largely symbolic) vote in parliament saw MPs vote 138 to 136 in favour of introducing proportional representation. If the government was to try and change the voting system, though, it’s unlikely the public would see a parliament-only move as legitimate. Three-quarters (73%) of the public say the public should decide on any proposed change to the voting system, with just 17% satisfied with MPs taking the decision in parliament.

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR: It seems great minds think alike. For more on the history of PR, I would recommend friend of Focaldata Sam Freedman’s recent piece on his Substack.

This post will cover our latest polling on Proportional Representation, exploring the stages of how we might conduct polling for a potential referendum campaign: looking at where public opinion sits, how a campaign might play out, what the next election could look like under PR, and what the implications might be for the future of British politics.

Where does public opinion sit?

While campaigners for PR may be buoyed by the seeming momentum behind the campaign for electoral reform, our evidence suggests public opinion is a lot more divided than many might think. Just a third of the public favoured changing the voting system for general elections when we asked the standard British Social Attitudes survey question, while 44% backed the status quo. When respondents are given an explanation of First Past the Post vs Proportional Representation [see appendix for exact wording], a plurality choose PR as their preferred system by a very narrow margin of 41% to 36% (with 24% unsure). Degree holders, Liberal Democrats and Green supporters, alongside those ‘very interested’ in politics are among PR’s strongest advocates.

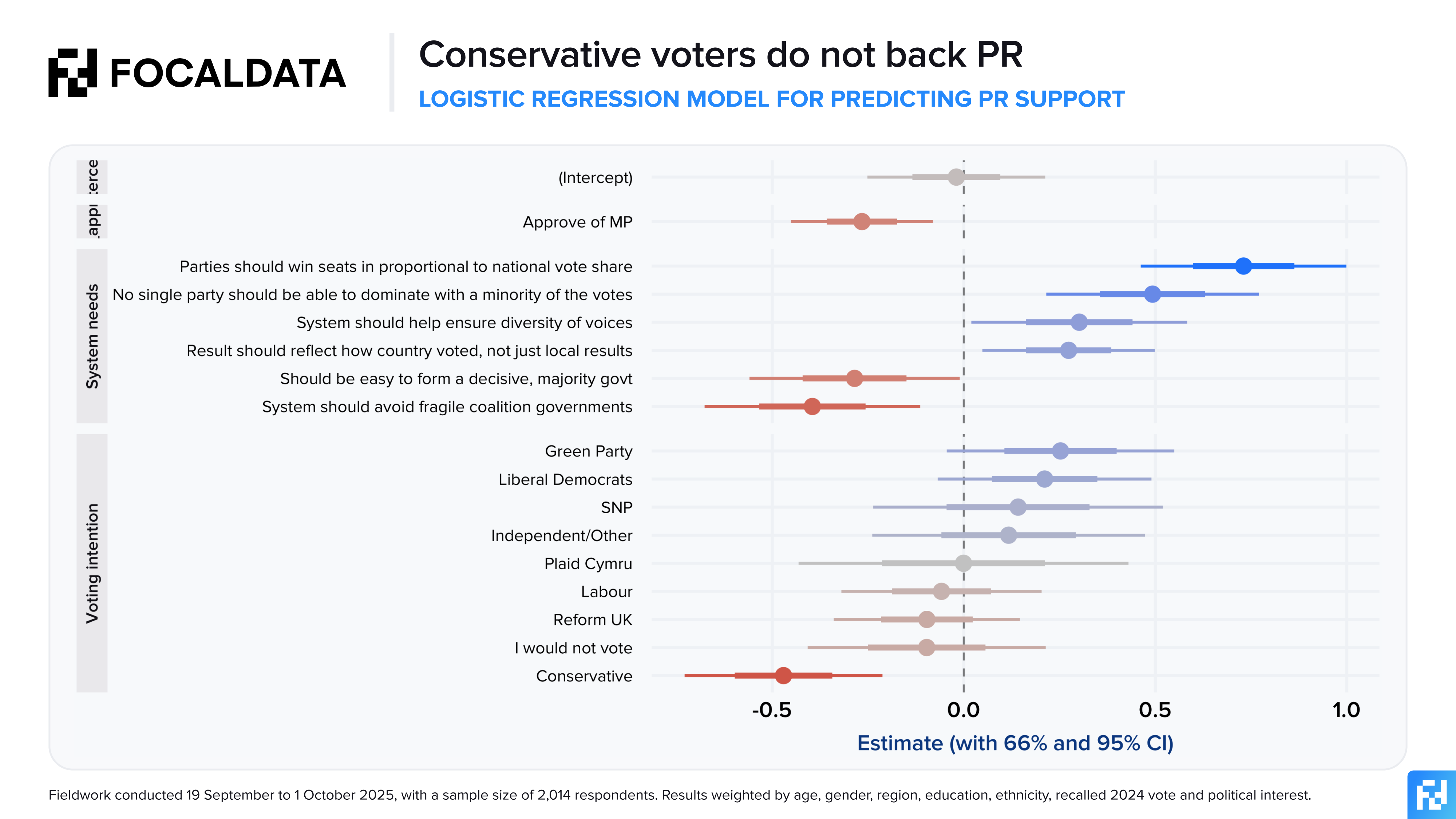

There is also a clear relationship between a person’s approval of their local MP and their tendency to support proportional representation. Support for PR climbs from a losing position of 40–54% among those who strongly approve of their local MP, to a near-2:1 landslide with those who strongly disapprove.

Putting things together, the model for predicting an individual’s support for PR vs the current system looks something like this:

The 41–36 headline split at this point tells us effectively nothing about how any future referendum campaign would go, and I would advise paying little attention to the headline numbers on any voting system questions right now. For context, campaigning organisations polling the UK’s membership of the European Union would have expected everything from a leave landslide of 52% to 30% (YouGov, August 2011) to a remain romp of 61% to 27% (Ipsos, June 2015).

Public opinion at this stage of an issue’s life cycle is simply far too volatile for us to be able to extract anything meaningful from the ‘horse race’ data. Any campaign analysis needs to go much deeper and create a suite of metrics to craft a much more robust estimate of where public opinion is likely to land on a given issue. That’s what we do for our clients in cases like this.

Fortunately for anyone reading this, we’ve already made a start on the heavy lifting, digging into what voters actually want from an electoral system and testing an array of different messages which would likely be rolled out in a referendum campaign.

What do voters want?

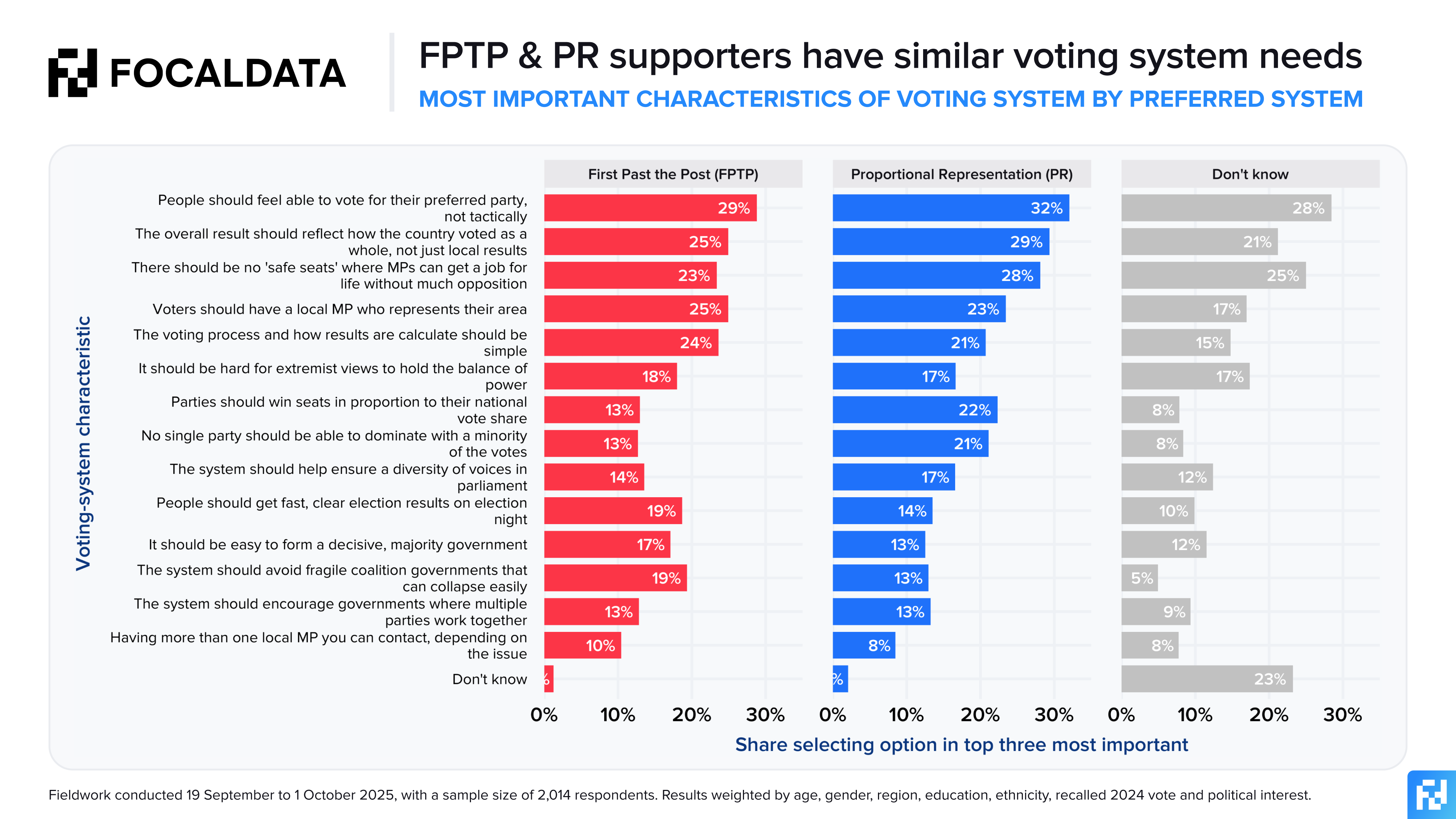

In contrast to previous referenda, voters’ underlying needs are remarkably similar on both sides of the debate. When people are asked for their top three priorities in an electoral system, the top four factors (albeit in different orders) are the same among both PR backers and FPTP devotees. Voters want to feel able to vote for their preferred party rather than tactically (32% PR, 29% FPTP); they want the overall result to reflect how the country voted as a whole, rather than just local results (29% vs 25%); they oppose ‘safe seats’ where MPs can get a job for life without much opposition (28% vs 23%); and they like having a local MP who represents their area specifically (23% vs 25%).

Out of fourteen characteristics, the only statistically-significant differences between the two groups are on parties winning seats in proportion to their national vote share (perhaps naturally), disinclination towards a party being able to dominate with a minority of the vote, and whether the system should disincentivise ‘fragile coalition governments’.

Looking at these numbers, I’d be happier on the PR side of the aisle. Overall, the top three needs are all more PR-friendly, and there appears to be more latent PR support among the undecideds (correlation coefficient of 0.46 with PR voters’ needs, compared to 0.37 with those of FPTP supporters).

But what does a referendum campaign look like when voters on each side have the same priorities and want most of the same things? I think it tells us a combination of the following:

- Views on the debate are, in all likelihood, very malleable. From the data, we think this issue is still in its infancy from a public-opinion standpoint, and is not yet close to reaching the polarisation stage that most major issues go through in their life cycle. Head-to-head figures on the public’s preferred system are likely skewed by low engagement or misunderstandings about what is actually at stake.

- In contrast with the EU referendum, the campaign around PR could be a debate around means rather than outcomes. What made the Brexit debate so potent was that it felt like a clash of two opposing outlooks on the world – should we heavily reduce migration or take a more liberal approach (parking what’s happened in the decade since)? Should we aim for full legal sovereignty or are we happy to sacrifice some of that if it means greater influence in Europe? Do we situate ourselves in a national culture or an international one? Here, the public seems to agree on what they want, but not on the means through which to achieve it. This has implications for campaigning organisations and those doing their comms. Voters are uniquely placed to shift in one direction or another on this issue, meaning the messaging approach needs to be different from a typical campaign.

Testing the messages

To assess the resilience of each system to the to and fro of a robust referendum campaign, our respondents were shown a selection of 16 arguments, which were an even mix of pro- and anti-proportional representation.

Our analysis found that arguments against proportional representation had a greater impact on system preference than those in support of it. Anti-PR messages reduce support for proportional representation by an average of 3.8 percentage points, but pro-PR messages only increase support by an average of 1.2 points.

On the PR side, the most effective messages are:

- “People shouldn’t have to vote tactically for the ‘least bad’ option to stop someone else from winning. Proportional Representation lets people vote for what they actually support.”

- “Huge areas of the country are politically ignored because the result there is seen as inevitable. With Proportional Representation, parties would need to earn votes everywhere rather than just focusing on swing seats.”

- “Millions of people’s votes go nowhere — either cast in safe seats or wasted on losing candidates. Proportional Representation means every vote helps shape the result.”

On the FPTP side, the most effective messages are:

- “First Past the Post gives everyone a single local MP who speaks for their area. Proportional Representation would blur that link, with MPs chosen from distant party lists instead of local communities.”

- “Britain is already politically polarised and regionally divided. Proportional Representation would encourage parties to form around narrow identities — religion, ethnicity, or single issues — forcing people into ever smaller boxes. First Past the Post pushes parties to appeal to the whole country, not just their own tribe.”

- “First Past the Post forces parties to appeal to the centre ground to win. Proportional Representation encourages fragmented, niche parties that don’t speak to most people.”

The full list of messages can be found in the appendix at the bottom of this post.

Message impacts differ significantly by party, however. A one-size-fits-all approach is less effective than tailored messages to different parties. Our modelling makes clear that messages perform best when tied to each party’s specific identity and policy beliefs.

Of the four largest parties, Reform voters are most susceptible to changing their mind depending on the message they are presented with. Labour are most clear-headed, with no messages currently changing opinion at the 95% significance level.

The most effective messages for Conservative voters are both anti-PR. The first is the idea that PR allows unpopular parties to cling on through coalitions, reflecting the party’s historic success winning majorities, and the other — the most effective — is the message about PR encouraging parties to form around narrow identities centred around religion or race, characteristic of some of the party’s MPs’ recent messaging around migration and a unified British identity.

For the Liberal Democrats, the self-professed home for many a centrist dad, the only significant message at the 95% confidence level was an anti-PR message extolling the virtues of FPTP in forcing parties to ‘appeal to the centre ground’.

Reform voters are the key swing voters in this debate, with two anti-PR and one pro-PR message causing significant shifts in preferences. As with Conservative voters, the ‘narrow identities’ message was significant, and Reform voters’ disconnection from Westminster and political disillusionment came through in the message favouring everyone having a single local MP. The most effective pro-PR message also plays on similar themes of anti-politics sentiment, arguing that voters should not have to vote tactically for the ‘least bad’ option. Dissatisfaction with the major parties is part of Reform’s appeal, after all.

No messages were significant at the 95% confidence level for Labour or Green voters.

The UK under PR

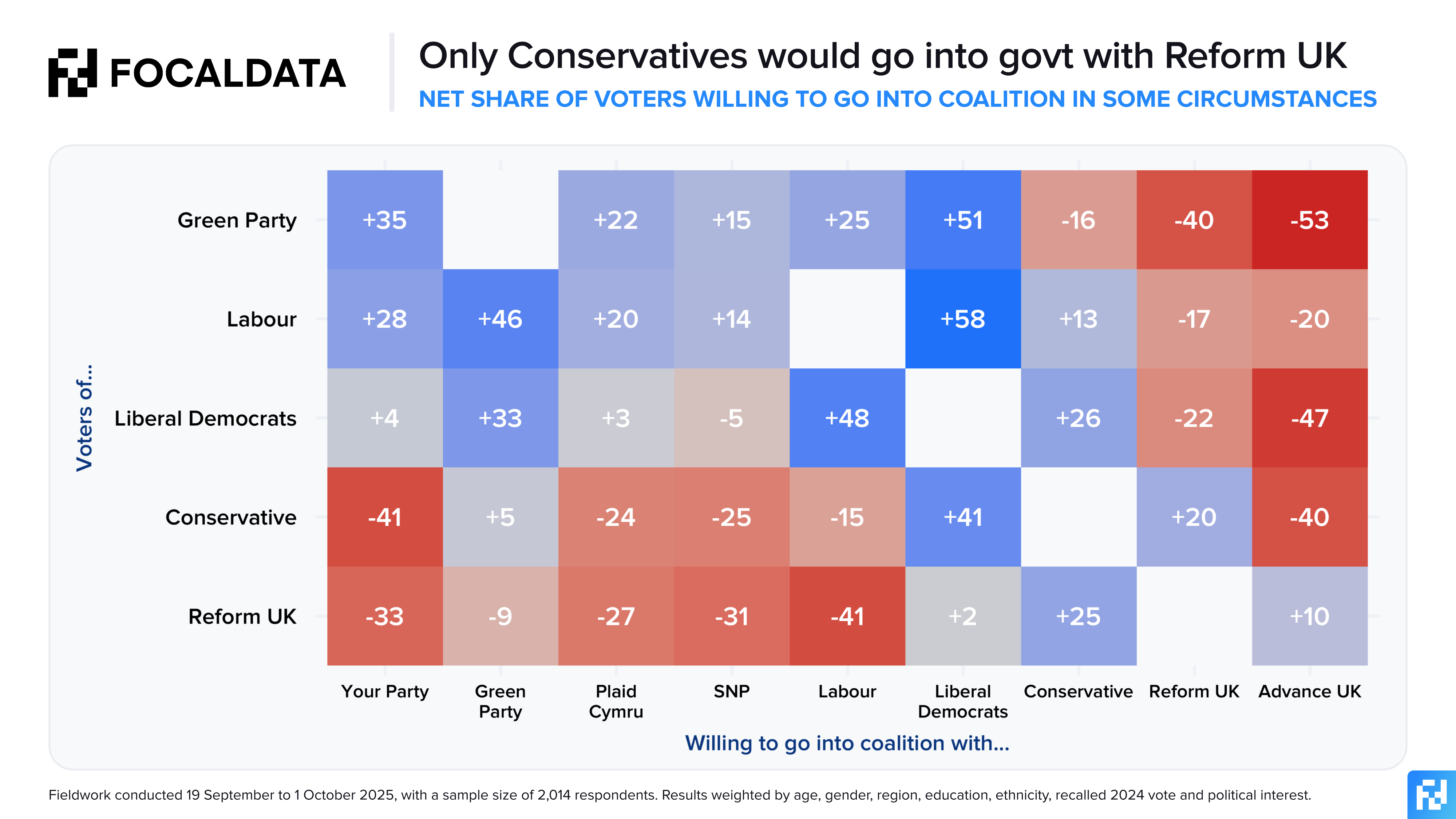

For the time being, let’s set aside the debate and suppose the UK implements PR before the next general election. In such a situation, the voting public is likely to split into two major left and right voting blocs. In the chart below, we calculated the net share of voters of each party who would be willing to go into government with every other party in at least some circumstances.

Voters of Your Party, the Greens, Plaid Cymru, the SNP, Labour and the Liberal Democrats all broadly appear willing to get together (though Lib Dems are narrowly opposed to an SNP coalition). On the flip side, the Conservatives and Reform are happy to collaborate.

In between the two blocs, one relationship stands out. Unbowed by the coalition era, Liberal Democrats would not rule out a coalition with the Conservatives, and vice versa. However, the Lib Dems draw the line at Reform UK, meaning a Conservative-Lib Dem coalition would likely need a majority of its own, sans-Farage.

The average voter accepts four or five different parties to go into coalition with at least some of the time. Labour voters are the most willing to be part of a coalition, with an average of 5.24 parties their voters would accept in some circumstances. The Conservatives, meanwhile, are the least willing, at 3.99 parties – perhaps a result of their historic electoral success as a majority-winning party.

We also asked voters to fill out a hypothetical ballot under a preferential voting system, to get an idea of the full voter flows. While the preferences look broadly as expected, some interesting things come out of this that once again prove that voters are a lot more complicated than many give them credit for: almost a quarter of Reform voters would rank Labour, the Lib Dems or the Greens second, and more Conservatives would put Labour or the Lib Dems second than Reform.

Nearly half of voters would not give more than two preferences, which reflects a common argument levelled against STV – that it preferences high-engagement voters and makes voting more complicated than it ought to be.

We used these preferences to build a model of what a general election held under a few different systems would look like today:

Single Transferable Vote

We created 128 multi-member constituencies to elect either five or six MPs under Single Transferable Vote (with the exception of island constituencies). Right now, STV would produce a small majority for a Conservative-Reform coalition (329 seats).

Party List PR (with 5% threshold)

Conducted on a regional basis, we used a 5% threshold at the regional level and calculated seats using the Sainte-Laguë method.

Party List PR (with no threshold)

Again, conducted on a regional basis, but with no threshold. Both Your Party and Advance UK would win upwards of 20 seats. Both party-list systems would result in wafer-thin majorities for a progressive coalition (320 or 321 seats before Northern Irish parties are accounted for).

Additional Member System

Using the D'Hondt system, we took the average share of additional seats in the London Assembly and Scottish Parliament and used that for our seat allocation, then scaled down the overall number of seats to 650. This system produces a tiny majority for the ‘conservative coalition’.

PR results

A move to proportional representation could see huge changes to the way politics and governing operates in the UK. Instead of high volatility, minoritarian governments that seem to be the new normal, we might be back to a majoritarian, coalition-building approach with a bit more stability in terms of policy platforms across governments.

We’ve been reflecting at Focaldata on some of our key findings from this year. Across a number of different issues, the polling we’ve conducted throughout 2025 alights on one key point: voters broadly agree that politics is broken. Whether they believe PR is the means through which to fix it remains to be seen.

Appendix

PR vs FPTP question wording

“In general elections, the voting system can affect how votes translate into seats in parliament. Two common systems are:

First Past the Post (FPTP): Each constituency elects one member of parliament (MP). The candidate with the most votes in each seat is elected, even if they don’t get a majority of the vote (i.e. over 50%). Supporters say it tends to produce stable, majority governments that can act decisively without needing coalitions. Critics say it can produce unfair results by giving parties a majority of seats without a majority of votes, and leaves many votes effectively ‘wasted’.

Proportional Representation (PR): Seats in parliament (i.e. the number of MPs) are distributed based on the percentage of the vote each party receives. For example, if a party receives 20% of the vote, it will win roughly 20% of the seats. Supporters say it leads to fairer outcomes, where parties receive seats in line with their share of the vote, so more voices are represented. Critics say it can result in fragmented parliaments and unstable coalition governments that make decision-making slower or less decisive.

Which voting system would you prefer?”

PR arguments

The UK needs action on the cost of living, housing and public services — not endless backroom deals. Proportional Representation risks months of wasted time forming coalitions every time we vote

In countries with Proportional Representation, tiny parties can hold governments to ransom in coalition talks. First Past the Post keeps extremists and single-issue cranks out of power

If a government isn’t working, First Past the Post lets voters kick them out decisively. Under Proportional Representation, the same unpopular parties can cling on through endless coalitions

First Past the Post gives everyone a single local MP who speaks for their area. Proportional Representation would blur that link, with MPs chosen from distant party lists instead of local communities

Changing the entire voting system would cost millions in new infrastructure, voter education and redrawn boundaries — money better spent fixing the NHS and public services

Britain faces big challenges that need decisive action. Coalition governments under Proportional Representation often struggle to agree on anything and end up paralysed

First Past the Post forces parties to appeal to the centre ground to win. Proportional Representation encourages fragmented, niche parties that don’t speak to most people

Britain is already politically polarised and regionally divided. Proportional Representation would encourage parties to form around narrow identities — religion, ethnicity, or single issues — forcing people into ever smaller boxes. First Past the Post pushes parties to appeal to the whole country, not just their own tribe

First Past the Post has delivered a failing political system with two stale parties at the top. People are fed up with the same faces, the same rows, and the same broken promises. It’s time to change the system and open politics up to new voices

Under First Past the Post, one party can win a majority of seats on less than a third of the national vote. Proportional Representation would make Parliament properly match the public’s choices

People shouldn’t have to vote tactically for the ‘least bad’ option to stop someone else from winning. Proportional Representation lets people vote for what they actually support

Huge areas of the country are politically ignored because the result there is seen as inevitable. With Proportional Representation, parties would need to earn votes everywhere rather than just focusing on swing seats

From the NHS to climate change, we need cross-party solutions. First Past the Post fuels tribal point-scoring. Proportional Representation would reward cooperation, not conflict

People have lost faith in Westminster after years of chaos, scandals and broken promises. Proportional Representation would give us a fairer, more honest system people can believe in

We’re a multi-party democracy trapped in a two-party system. Proportional Representation would reflect modern Britain rather than the outdated two-party system

Millions of people’s votes go nowhere — either cast in safe seats or wasted on losing candidates. Proportional Representation means every vote helps shape the result