Blog/In print

Making friends is what keeps us happy

My local neighbourhood has a monthly ritual, “playstreet”, when the road is closed to cars for a few hours over a weekend to allow children to enjoy themselves. The scene is idyllic, except for one detail. The call each month for people on WhatsApp to give up a tiny proportion of their time to supervise is met with near silence, except for a few hardened volunteers. My neighbourhood is rich in social capital and local relationships. If we struggle for volunteers, what is happening around the country?

There is a depressing decline in Britain’s social networks. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the church and trade unions — the social capital heartlands of the political right and left last century. Weekly church attendance hovers at roughly 700,000 people, down from 1 million as recently as 2009 (though that has begun to reverse in the last year or so). In 1979, one in four people were trade union members, today just one in ten are. Pubs, the crucible of many friendships, fell in number by 22 per cent between 2001 and 2019.

As the physical and social infrastructure of our country has weakened, so have attitudes towards civic engagement. The Community Life Survey suggests just 16 per cent of people engage in formal volunteering once a month, down from 27 per cent 12 years ago, and civic participation is down 10 per cent from the height of Covid, according to the same survey.

Robert Putnam, the leading scholar on social capital, argued in his seminal work Bowling Alone that “kids today aren’t joiners”. In doing less we meet fewer people and create fewer connections. The think tank Onward produced research in 2021 which found a depressing cohort effect: over-65s today are nearly three times as likely to say they have six or more close friends than under-25s (at 14 per cent).

In the middle of a cost of living crisis and Trump-inspired geopolitical uncertainty, our attention is now shaped like an hourglass. We are relentlessly focused on our families’ immediate needs, the nation and world’s troubles but nothing in between. Instinctively this makes sense. Yet is it a good thing? Can we expand the thin middle of what we might call the “hourglass society”?

Nobody is ever going to argue that the bloke they meet three times a year for a cricket match is the most important relationship in their life. But we have vastly underestimated the power of acquaintance, and of outer circles of empathy and human connection that a life rich in social capital provides.

Last month Putnam spoke at the launch of a British study into social capital, based on data from 20 million Facebook users and the six billion relationships between them. The team of researchers was drawn from the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) along with the tech firms Meta, Stripe and the Behavioural Insights Team. This potentially seminal study argues persuasively that social mobility is linked to the social connections between high and low income earners. The research also found that the number of cross-class friendships and overall number of friends is predictive of life satisfaction and trust in others. Social capital is the stuff of life.

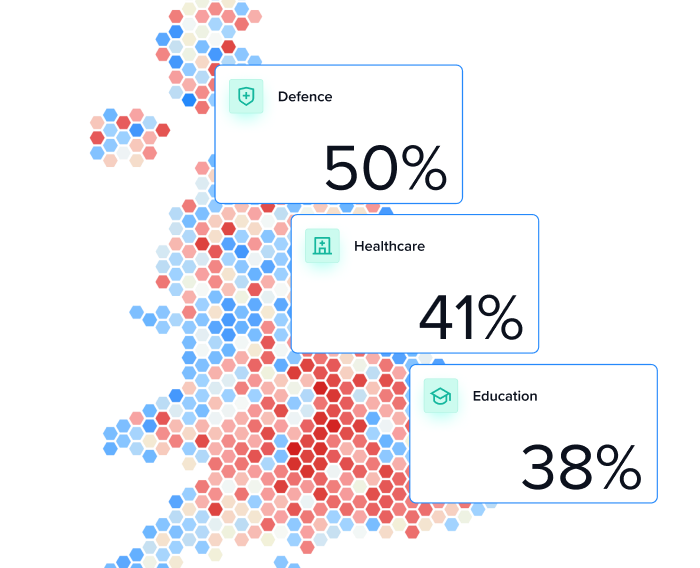

The report shows how civic strengths and weaknesses vary around the UK. “Bridging capital”, defined as the degree of cross-class connection and social mobility, is much stronger in the south than elsewhere in the UK. But when it comes to “bonding capital”, defined in the paper as the share of friends who are also friends with each other in any given area (a proxy for interweaving webs of relationships and solidarity), the UK’s Celtic fringe — Cornwall, Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland — show the strongest prevalence of bonding social capital.

So which areas have neither? My firm Focaldata’s modelling suggests that the lack of bridging and bonding capital can be a consequence of a lack of wealthy people and a community having to absorb high levels of immigration, particularly where integration is low. Both the present and previous government had no good answers on either challenge.

It’s not all doom and gloom though. Initiatives are taking root to replace the civic architecture of the past. Look to your local park and you’ll encounter millions who are registered for Parkruns. The National Trust still has a five million strong membership, and the Co-op group a similar number.

But it’s perhaps at the smaller level — the humble hobby — that Britain can mend itself. You might think that Games Workshop or ultimate frisbee have nothing to do with our nation’s civic health, but you’d be wrong. The RSA’s researchers found that hobby groups were the place where you were most likely to connect with different people.

Encouraging people to start hobbies might sound like a very British solution to the “bowling alone” problem. But there is something innate in our character that enjoys social connections and hobbies. It’s no wonder that James May, the former Top Gear star, has found great success in presenting TV programmes devoted to British pastimes both strange and boring.

The challenge is getting political leaders to talk about the benefits of a book club when the West is facing material economic decline. Politics repeats itself; just 15 years ago David Cameron’s Big Society campaign for stronger civic infrastructure was politically relegated when geopolitics and a recession came to the fore. Our leaders need to be on the front foot to prevent that happening again. All of us, in some way, are searching for a sense of home.

Article originally appeared in The Times.