Blog/In print

Reform threatens to wipe out the Tory party

Picture this once unimaginable scene. It’s the next election, say May 2028, and a chastened Sir Keir Starmer returns to No 10 some 70 seats down, claiming a tiny parliamentary majority with fewer than 30 per cent of Britain’s votes. Labour’s gossamer mandate isn’t the story though, it’s Reform’s new 100 MPs, heralding the end of the Conservative century as a dominating political force, putting them behind Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Nigel Farage declares that the 2030s will be the “decade of Reform” and he will one day soon be prime minister.

This chaotic 2028 outcome might still seem outlandish. It is less probable than not. But it could absolutely happen. The Conservative Party is on political life-support — and the party should not kid itself otherwise. The Tories hold only 44 seats with a victory margin of more than 10 per cent, compared with 51 Liberal Democrat seats. Labour is simultaneously grappling with its wide but shallow “sandcastle” political coalition, vulnerable to erosion from Reform on the right and the Greens on the left. If the Reform surge of 2024 continues, the traditional main parties could decline in parallel to allow Farage’s army to materially break through.

Reform is not a party that should be embraced with open arms by Conservatives. It has candidates with deeply problematic views and has injected venom into our discourse that has coarsened debate and made consensus on the most sensitive of issues much harder. Reform, though, is a creation of Conservative failures. Those who don’t wish to see it become a permanent fixture should take its success and supporters seriously.

So how did this opportunity for Reform arise? A key reason, detailed in a report by the think tank Onward, highlights the Conservatives’ reliance on a crucial set of voters who share some “super-demographics”. These voters are some combination of over 55, Leave-voting, not university-educated, suburban, from skilled working-class households, and homeowners.

Critically, these voters are politically volatile, pinging multiple times from 2010 to 2019 between Conservative, Labour and Farage’s three entities. These voters are evenly distributed across the country, acting as political kingmakers across huge swathes of Britain. They shifted en masse towards the Conservatives in 2019, but abandoned the party for Reform and the Liberal Democrats this year. Support for the Conservatives among these voters surged by over 30 percentage points after 2015 but plummeted by more than 40 points this year.

Conservative fortunes among these “super-demographics” explain much of British politics since 2010. From the collapse of the Liberal Democrats in their rural heartlands in 2015, to the 5 per cent Tory vote gains under Theresa May in 2017 — particularly in Wales and Scotland — and eventual 2019 red wall gains made by Boris Johnson, all of these vote increases were driven by the same groups of voters. On July 4, the Conservative Party saw six election cycles of super-demographic gains wiped out in one catastrophic moment.

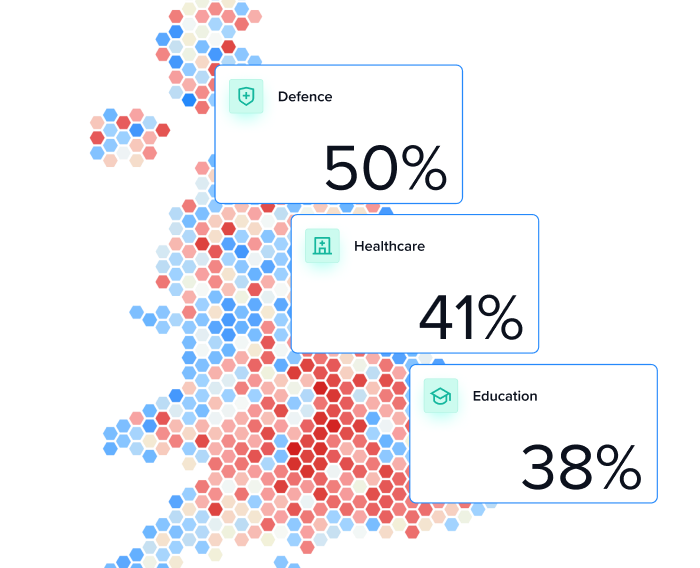

But things could deteriorate further for the Conservatives. Focaldata’s modelling suggests that Reform (4.1 million votes last month) and Ukip (3.9 million votes in 2015) are not identical beasts. Across the Midlands, Teesside, northeast Scotland, the Welsh borders, Essex and Lincolnshire, Reform’s vote share in 2024 far exceeds that of its predecessor in 2015. This matters because these areas are the soul of the modern Conservative Party.

The threat of Reform for the Conservatives is akin to the tussle between the SNP and Scottish Labour after the 2014 independence referendum. The electorate could twist and turn in a similar fashion over the next decade but Farage has a number of political tailwinds that could plump his party further.

First, Reform’s brand is unencumbered by the brand destruction the Conservatives suffered among younger voters. Ipsos Mori found that the Conservatives were in fifth place among voters under 35 while Reform came second among 25 to 34-year-olds. Farage won nearly 30 per cent of younger voters in skilled working-class jobs.

The challenges facing many western democracies are better suited to Reform’s blunt form of social politics. From immigration and integration to sectarian voting and the rise of DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) issues or the affordability of net zero, Reform can more naturally play the antagonist to Labour’s protagonist. Most crucially, Reform’s traction among super-demographics means there is no reason its vote share cannot rise further above 30 per cent over the next parliament.

Yet it may prove that Reform’s greatest threat is Reform. Infighting, foreign policy and an inability to build local government infrastructure may provide an electoral ceiling. A movement that has changed its name and branding three times in four elections hints at lack of durability. The Conservatives, meanwhile, are still negotiating visitation rights to the electorate — granted reluctantly by a media who don’t want to cover yesterday’s people.

In this environment, Aristotle provides some unlikely inspiration to the Conservative Party. His classic theory on persuasion had three parts: the logic and consistency of an argument (logos), your ability to connect with people’s values and beliefs (pathos) and the credibility and standing you have to persuade (ethos). Having persuaded about a quarter of voters and only one in seven working-age adults to vote for you, where do the Conservatives start?

Instead of a navel-gazing exercise on the merits or wrongs of the past 14 years, the Conservatives should focus relentlessly on an intellectual offer (logos) first, and only then sketch out a path to persuading the country (pathos) of its values and vision. Rebuilding trust and credibility is really an output of the entire process.

Policy objectives constantly changed and incompetence became the only constant over the past 14 years. Crucial questions such as the role the state plays in people’s lives, the optimal rate of tax, where to build houses, public service reform, and levels and types of immigration are still being debated after 14 years of government. If Conservatives do not know why they exist, except to keep Labour out, voters will eventually figure out the self-serving nature of the project.

Reconstructing the intellectual pillars of Conservatism may look like an inward extravagance faced with a resurgent Reform party and a Labour government leaning into its executive power. But that’s the test: who is brave enough to do the internal plumbing of politics? Without this, how can the Conservatives hope to win over the super-demographics again? If they do not, Reform, Labour and the Liberals can surely carve up Britain between them.

Article originally appeared in the The Times