Blog/Analysis

Short attention spans are ruining politics

Why is a car numberplate around seven characters long?

In 1956 George Miller, a Harvard psychologist, provided a clue. Miller’s seminal academic paper claimed that people’s short-term memory span for recalling distinct items in order was capped at around seven.

If our working memories, as Miller suggested, are finite then the information explosion driven by technology has led to attention becoming one of our most scarce resources. Two of the academics that Miller inspired, George Loewenstein and Zachary Wojtowicz, have argued in a recent paper that the attribute of attention should be included alongside physical factors such as land, labour and capital as a resource that drives the “wealth of nations”.

Their main contention is startling:attention is the new gold. In the economy of clicks, hits, eyeballs on screens, short-form work, art and entertainment — whatever gets your dopamine levels up — attention shapes everything. We now, on average, spend 25 years of our lives staring at screens. For the next generation, it is worse. The Institute of Practitioners in Advertising showed that under-25s will spend 16 years of their lives staring just at their phones.

The battle for our attention waged by different technologies, platforms and content has transformed politics, economy and society — mostly for the worse. We are overdue a movement aimed at helping society take back control over how we allocate our attention.

The costs of attention becoming scarce in politics are high. Grabbing time is what has incentivised extreme content across our screens; coarsening and simplifying the political debate, while elevating fringe individuals into the heart of mainstream conversation.

Some of the effects of our attention-scarce society have been subtler. The polling firm More In Common has recently identified one of the key political swing groups in Britain as the “sceptical scrollers”, the first time a British political segmentation has included people’s attention allocation.

With our attention spread thinly, it is clear that people prefer to engage with social and cultural content more than economic content.

Much of this summer’s discourse has been dominated by whether or not we should welcome the proliferation of Union Jacks and St George’s flags on lampposts across the country. This is a debate that sits at the heart of our national identity, but where is the passion and emotion around our terrible debt and fiscal position?

Some will say that the public never cared much about economics, but research I carried out a decade ago indicated that attitudes to the size of the tax burden usually moved in lockstep with actual public spending as a percentage of GDP. When the state was too big, people warmed to cuts. When it was too threadbare, the public moved towards investment. Returning to the data since 2020, this 30-year-long trend has weakened severely. Spending remains high — well over 40 per cent of GDP — but appetite for even more largesse is still there.

The lack of honest trade-offs is a distinct feature of an attention-scarce society. Adverts for printers, mobile phones or banks routinely take advantage of consumers’ limited attention by strategically obfuscating the price of add-ons. Think about the long-run recurring cost of printer ink, mobile tariffs or ATM overdraft fees. Corporate winners regularly run at a loss on their upfront offer and capture wallets later, which time-poor consumers don’t notice.

In the commercial sphere these arecalled “shrouded attributes”. And once you understand what a shrouded attribute is, you see them everywhere in politics: big promises today, for which you only get hit downstream. Our “buy now, pay later politics” has created huge liabilities, usually off the back of a policy that is too good to be true or whose true liabilities are hidden.

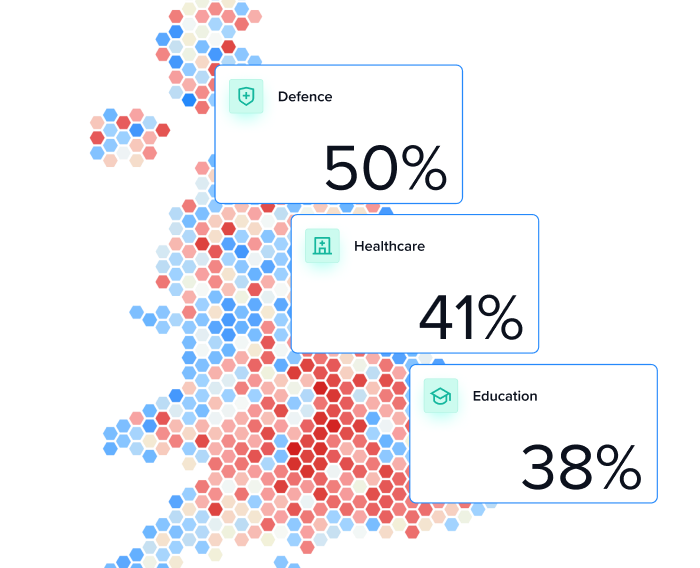

If you want to understand how our attention-scarce society has damaged government, look at how important issues have been ignored by the state. Housing, according to YouGov, is considered a top three issue by only one in six voters. Transport has been considered atop priority by only about 3 per cent of the public since 2011. It is no wonder we have failed to make the progress needed to keep Britain a wealthy, well-connected and well-housed nation.

Emotive issues draw on our attention, and therefore the public purse, which is how the detailed issues that drive the wealth of nations are neglected; whetherthat’s procurement, falling birthrates, energy costs or housebuilding. It should not be a surprise that faith in liberal democracy is fraying when politicians find it so hardto focus on getting stuff done for the long term.

So how do we elevate the boring, the technical and the long-term?

The first step is to realise that voters don’t want politicians who mirror their thoughts, they want politicians who solve their problems.

A case in point is Nick Gibb, the former Tory schools minister, who has just published a book showing what a successful political career with strong attentional focus looks like. Serving 15 years as shadow then actual schools minister, his reforms to how language is taught and what the curriculum consists of provided a standards revolution in English schools. That was the result not of trying to court popularity — education has been a top issue among only 13 per cent of British voters since 2011 — but of detailed policy work.

A case in point is Nick Gibb, the former Tory schools minister, who has just published a book showing what a successful political career with strong attentional focus looks like. Serving 15 years as shadow then actual schools minister, his reforms to how language is taught and what the curriculum consists of provided a standards revolution in English schools. That was the result not of trying to court popularity — education has been a top issue among only 13 per cent of British voters since 2011 — but of detailed policy work.

This month, as millions of schoolchildren return to the schools that Gibb helped transform, many pupils won’t be allowed to take their mobile phones into the classroom.

What’s good for children might just be good for us too.