Blog/Analysis

Agency could be the next big idea

“Can you tell me any good news? Literally anything?” is the question I hear most often in the UK. I’m tired of merely pointing out depressing trends (see the appendix) so I have some semi-good news. Broadly, it is a semi-thesis about why we are an unhappy country and a potential route out of our malaise. The short answer from my polling analysis is that our national happiness requires making Britain rich again, and cultivating/nurturing high-agency people and institutions in Britain. These are not necessarily separate things in practice – there may well be a dynamic feedback loop – but for the purposes of analysing public opinion they are separate.

The first part of the equation – making Brits richer on a per-capita basis – is about better parameters in which positive social contexts happen more frequently (more people in their own homes, higher pay, lower, and more skilled immigration levels, nicer streets, better public services, stable families). The second part, creating a high-agency culture, is less obvious, and is critical to individuals and institutions having the freedom to basically improve their own circumstance and place. I think most people are not that familiar with agency as a concept so here’s my take.

What do I mean by agency?

Cate Hall is a pretty extraordinary character (ex #1 world female poker player, ex addict, ex supreme court advocate) whose Substack on agency I stumbled on in recent months. Her experience of addiction is a critical piece of writing about personal reframing and how to inject agency into a situation without any change in material assets. Her thinking is more developed and US-tinted than mine, but in an interview I had with her this week she described agency along the following lines:

“The ability to see and act on the capacity to act on the degrees of freedom that anyone has”. Another framing she uses is “manifest determination to make things happen”.

In a polling context I’ve taken it to mean “how much freedom of choice and control do you feel you have over the way your life turns out?” It turns out when you ask this question of the British public on a scale of 0 to 10 they come out at an average of 6.3. Not bad, but roughly 20-30% (depending on your cut off point) of the public basically think they are without agency. Sobering.

The growth of agency-suppressing views seems to have dovetailed with the actual collapse in growth and living standards amongst huge cohorts of the public so that we have more people than ever who feel they are at the bottom than before, which, given the concept of an average, is definitionally impossible. That’s what I defined in my last blog as the “Nietzschean trap”: “But the most pessimistic trend I’ve observed over the past decade has been the arms race in more and more Brits seeing themselves as ‘left behind’ in some way and not captains of their own destiny.”

I’ve co-authored this blog with my left-voting colleague Patrick Flynn. I did this because the issue of the UK’s grievance industry is too important for this to become a left-right issue. I was also incredibly keen for it to not become a hackneyed centre-right piece on “bootstrap” politics and check my own priors. Ultimately I don’t think we’re here by design. I don’t think anyone decided to create the perfect conditions for a very unhappy country. The Nietzschean Trap is something made possible by the decoupling of “privilege measures” of land, inheritance, health, wealth, income, cultural power, education, personal resilience and job security. Everyone can now find a dimension in which they are the underdog, and their personal life story is overcoming great obstacles to achieve against the odds. If everyone is left behind then surely nobody is. The Nietzschean trap has ensnared people from across the spectrum.

The Nietzschean trap: The exhibits

- Some of the highest income parts of the home counties which with high concentration of leave voters were able to claim the mantle of “left behind” at the 2016 EU Referendum (but curiously not Remain Merseyside or north Haringey)

- Activists that occupy organisations like Extinction Rebellion - with millionaire backgrounds and names that reveal as much using macro-trends like climate change to re-imagine themselves as generational underdogs

- How literal princesses talk about the difficulties of being company founders

- People explaining their lives in reference to their parents’ lives and not their own

- Where people vastly underestimate where they sit on the income spectrum

- A world where millionaire pensioners get free bus-passes

- DEI schemes that allow some individuals with massive amounts of cultural power and income to gain access to jobs others with less resources can’t use

The “Nietzschean trap” has been devastating to the West. Literally anyone can self-define as victim rather than victor. My hypothesis is that by reducing the role of personal agency in self identity, people are becoming unhappier, less optimistic, less trusting and less capable. We also end up ignoring the people who really, really need help. We’ve run a survey and conducted statistical analysis to look and test this hypothesis.

What did we test?

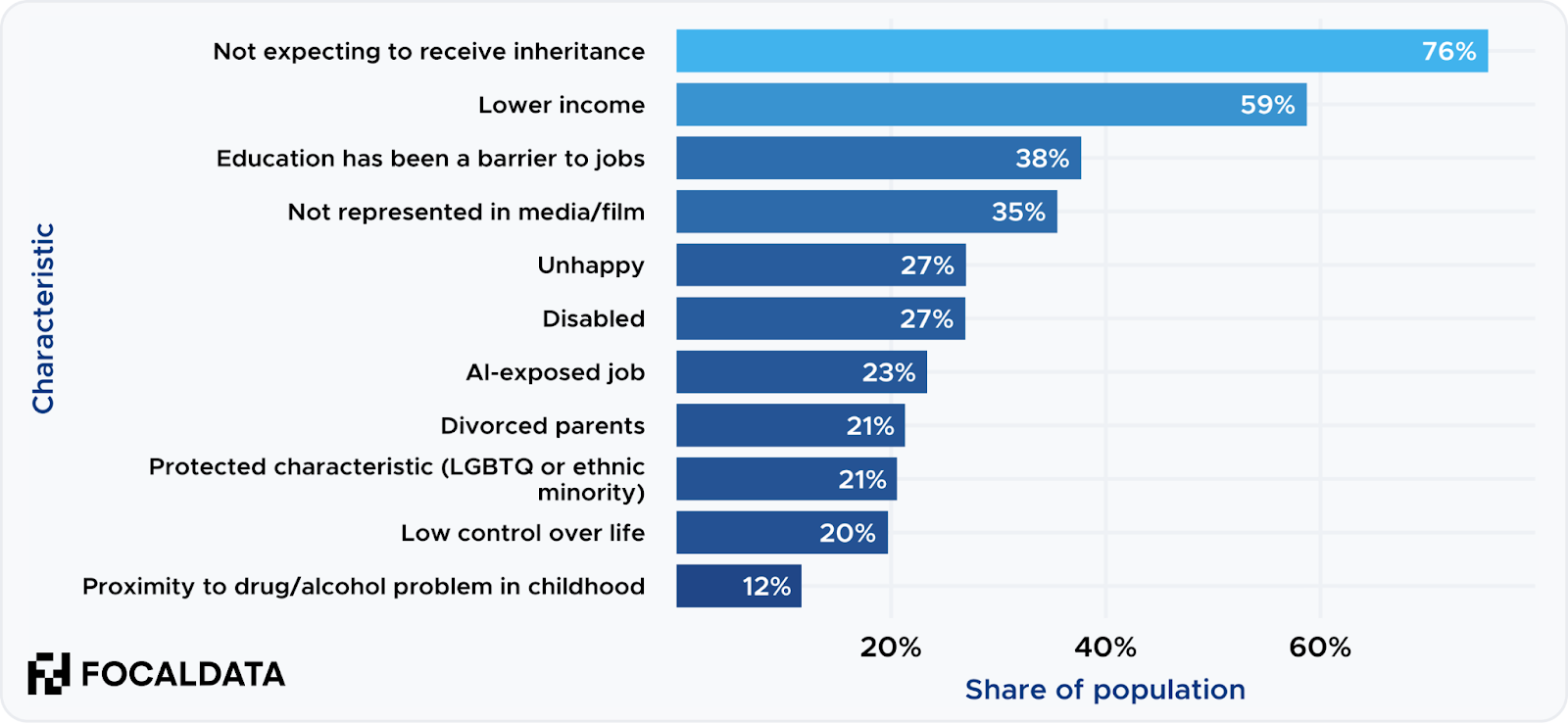

Firstly, we looked at a whole battery of statements from the public on which they could claim as being left behind in some dimension, from the objective – i.e. income – to more subjective areas like control over their lives or happiness.

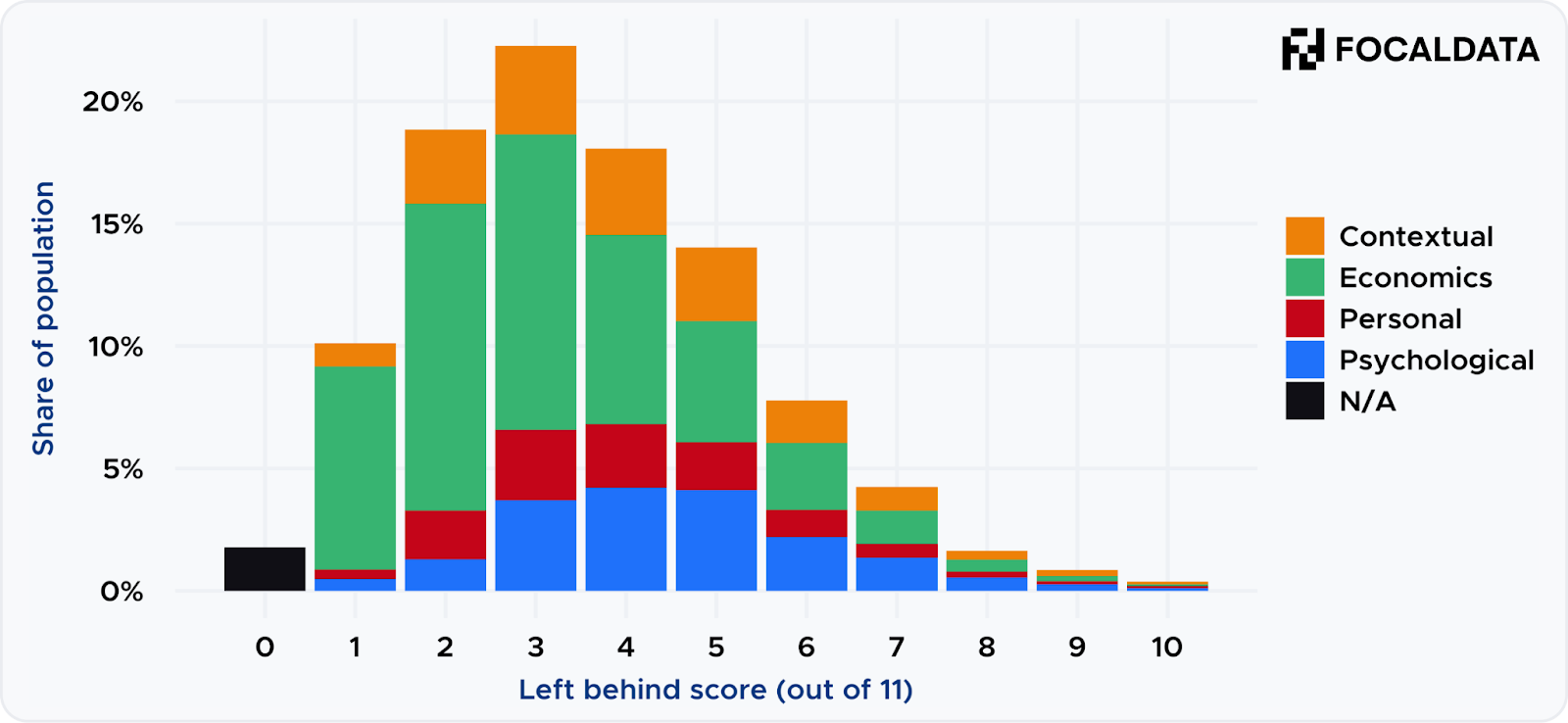

Then we wanted to see how many people scored on each ‘left behind’ measure. The median measure is 3 out of 11 possible categories, but it’s a left tailed distribution. Most people are not that high in victimhood, but there exists a heady band of people with multiple claims.

Having examined different aspects of what it means to be “left behind” I was interested to see what the relationships were on belief sets that are an unalloyed bad for individual and societal happiness and success.

We looked at a wide variety of attitudes, sentiments and dispositions: zero-sum thinking (see this Havard paper), characteristics of anxiety and depression, rumination and ‘dark triad’ beliefs like narcissism. Fundamentally the most important “dependent” variables of life for happiness and success are the ‘OATs’ – Optimism, high Agency behaviour and Trust in others. I wanted to understand how prevalent these postures are. Do they appear amongst similar people?

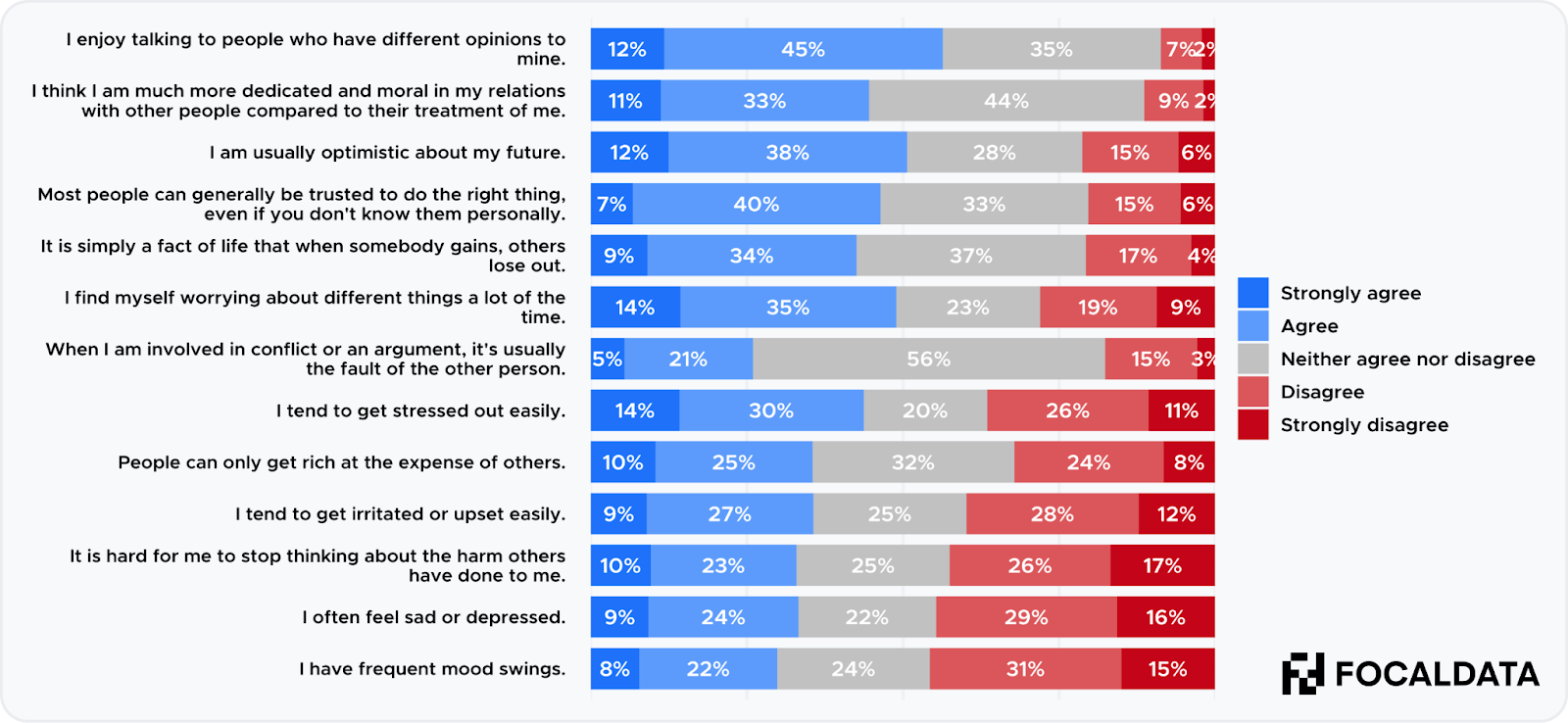

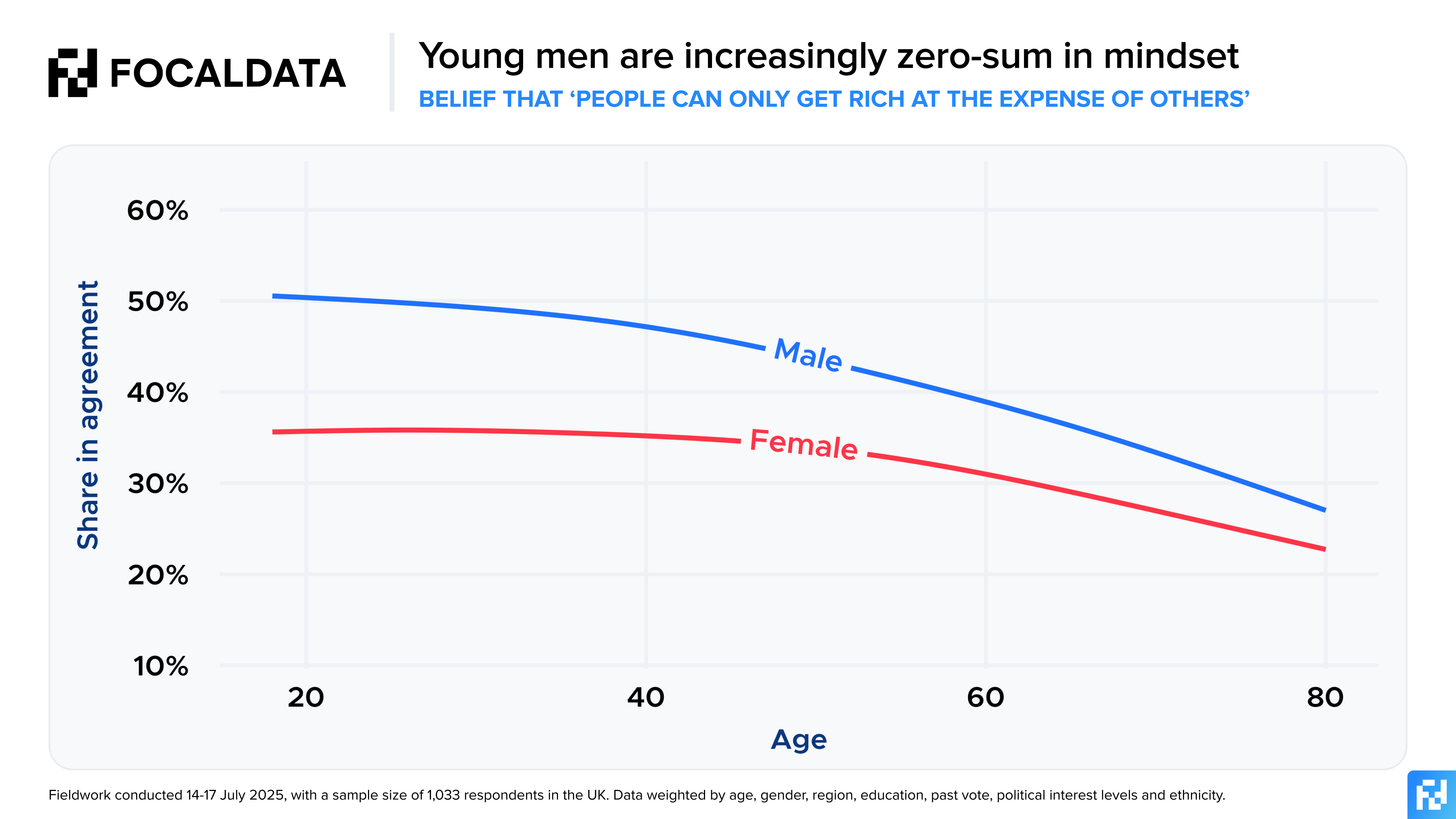

The first bit of news isn’t good – negative thoughts are prevalent across Britain, with a growing problem in the younger age groups. Nationally, 35% agree with the zero-sum belief that ‘people can only get rich at the expense of others’, but that rises to 51% among young men. We know that zero-sum thinking is tied to GDP growth in childhood, so it’s understandable that younger people would be more inclined to believe it, but that doesn’t explain the growing gender gap:

This dynamic parallels the increased division between young men and women’s voting intentions across the West in recent years, with males increasingly opting for radical right parties. The UK is one of the less extreme examples of this, but the gap may grow in future. Our latest voting intention of 16 and 17 year olds, for example, saw 25% support for Reform among young men, compared to just 10% among young women.

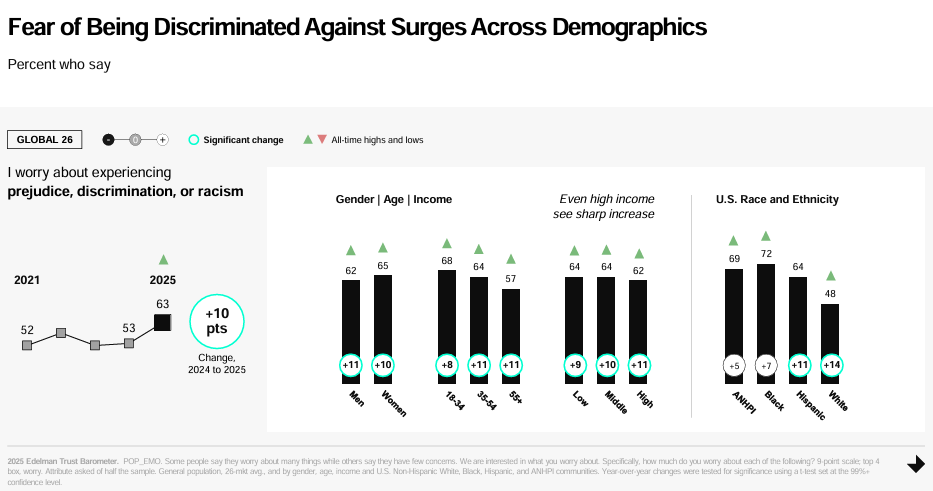

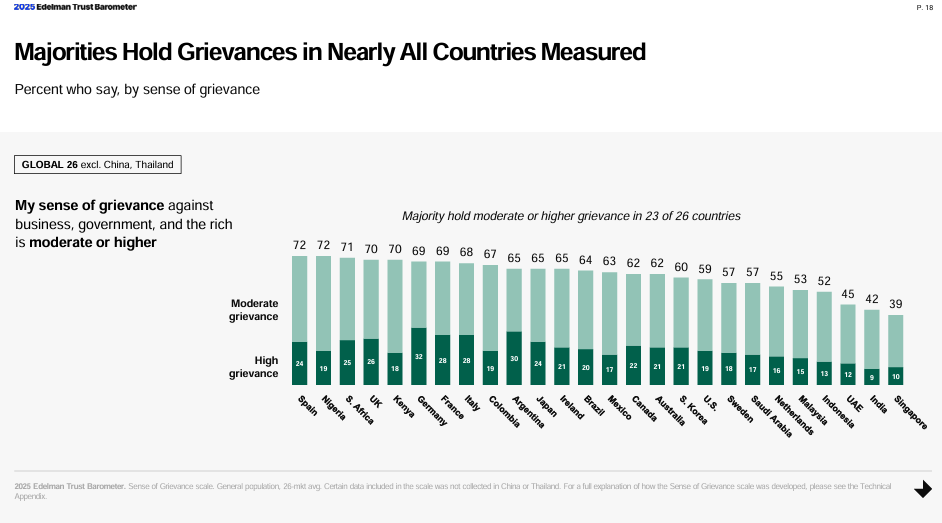

Across other statements, 44% of the public say they tend to get stressed out easily, and 49% find themselves ‘worrying about different things a lot of the time’ – with both figures rising to 62% among women under 45. A third (33%) of Brits ‘often feel sad and depressed’, the same share who say it is hard for them ‘to stop thinking about the harm others have done to me’. Almost half (45%) take the low-trust view that they are ‘much more dedicated and moral in my relations with other people compared with their treatment of me’, climbing to 59% among men under 45. Just 11% of Brits disagreed. The public affairs firm Edelman have done some fantastic work on a lot of this and call it the global “crisis of grievance” which very much represents my concept of the Nietzschean trap and its build-out of his concept of "ressentiment" The UK is in horrifically bad shape when it comes to industrial-scale ressentiment.

Thinking about this crisis of grievance we wanted to understand better how psychological thought patterns, senses of grievance, optimism and politics all interacted with each other. The first thing I wanted to do is look at the role of "neuroticism".

We combined eight statements covering four psychological thought patterns:

- Anxiety: ‘I tend to get stressed out easily’ and ‘I find myself worrying about different things a lot of the time’.

- Depression: ‘I often feel sad or depressed’ and disagreement with ‘I am usually optimistic about my future’.

- Narcissism: ‘I think I am much more dedicated and moral in my relations with other people compared to their treatment of me’ and ‘When I am involved in conflict or an argument, it’s usually the fault of the other person’.

- Capriciousness: ‘I have frequent mood swings’ and ‘I tend to get irritated or upset easily’.

Based on agreement with these statements, we created an index of what the ‘Big Five’ personality model calls neuroticism (while ‘neurotic’ can carry negative connotations, we are using the term in a neutral, psychological sense here rather than casting a value judgment).

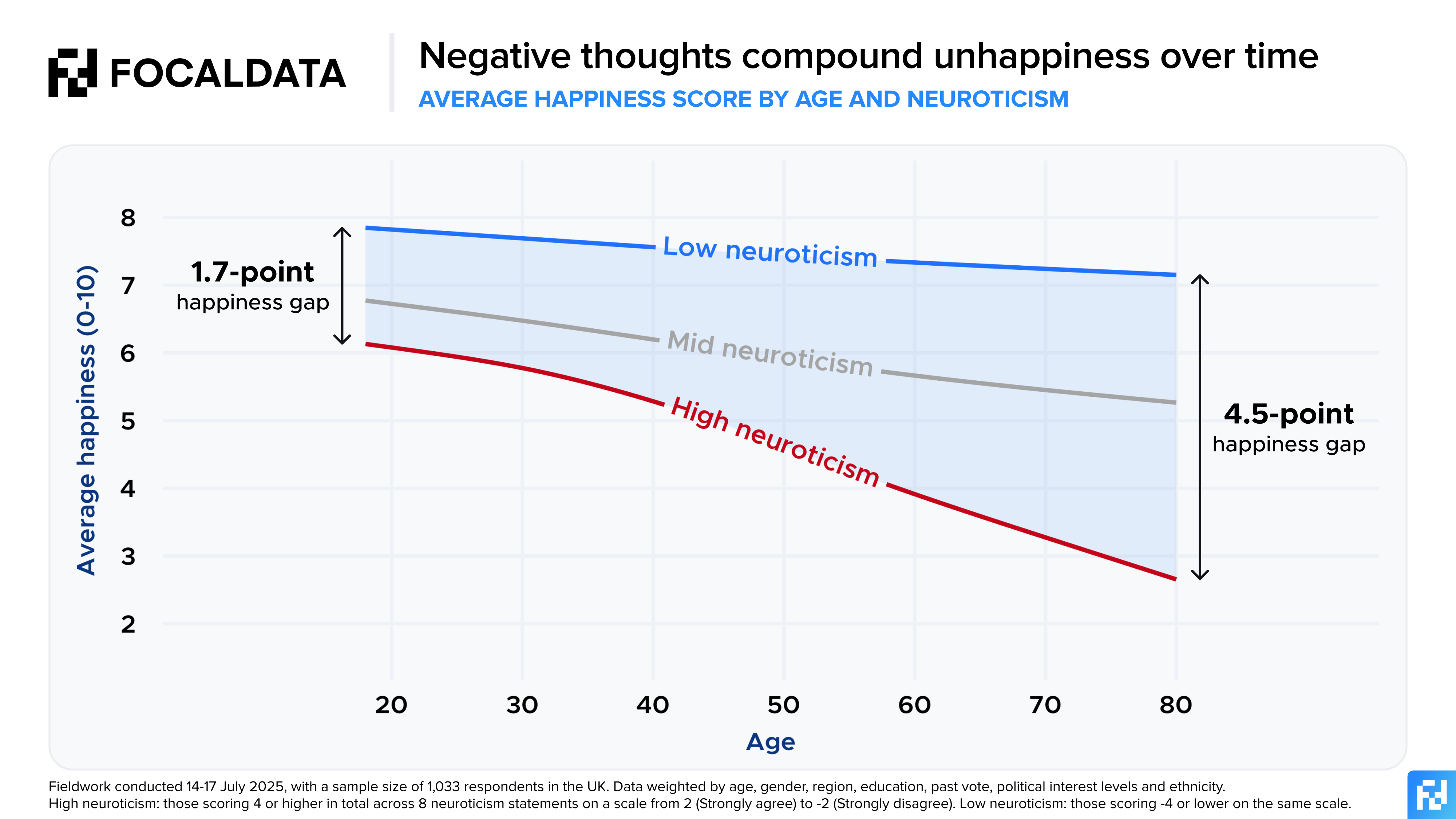

One striking – and deeply worrying – statistic that we found is that these thoughts have a compounding effect on happiness over time. Young people with higher levels of neuroticism see a large reduction in happiness as they age, whereas those with lower levels see little-to-no reduction. On average, those over the age of 60 with high levels of neuroticism score their happiness at just 3.3 out of 10.

Now why does this happen? As people age, long-term cognitive habits can impact relationships, jobs, and other aspects of life, affecting overall happiness levels. If young people carry these thoughts as they age, overall societal happiness could collapse over the next few decades. It is essential for the country’s future happiness that we find a way to prevent anxious young Brits turning into a generation of unhappy middle-aged people. The government and wider society need to find ways to address these kinds of thought patterns early among the next generation. My co-author Patrick’s fusillade of suggestions included better mental health provisions, high-quality free therapy for under 30s, French-style social media restrictions for teenagers or mandatory membership of at least one social club. My own priors lead me more towards reducing mobile phone addiction (James Marriott can lead this campaign), more in-person social contact and addressing ideologies that tell otherwise comfortable, privileged people that they have essentially been wronged in every possible way. The question over how to basically deconstruct and reduce national anxiety levels is a kind of Rorschach test of politics. How can we make Britain happy then?

The happiness formula

What if we could create a formula for happiness? Using all our respondent data, we did just that. We wanted to ensure that our model was based on things which can actually be changed (so it doesn’t include age, for example) or things that are a proxy for happiness (like optimism and trust, and we hypothesised being high agency).

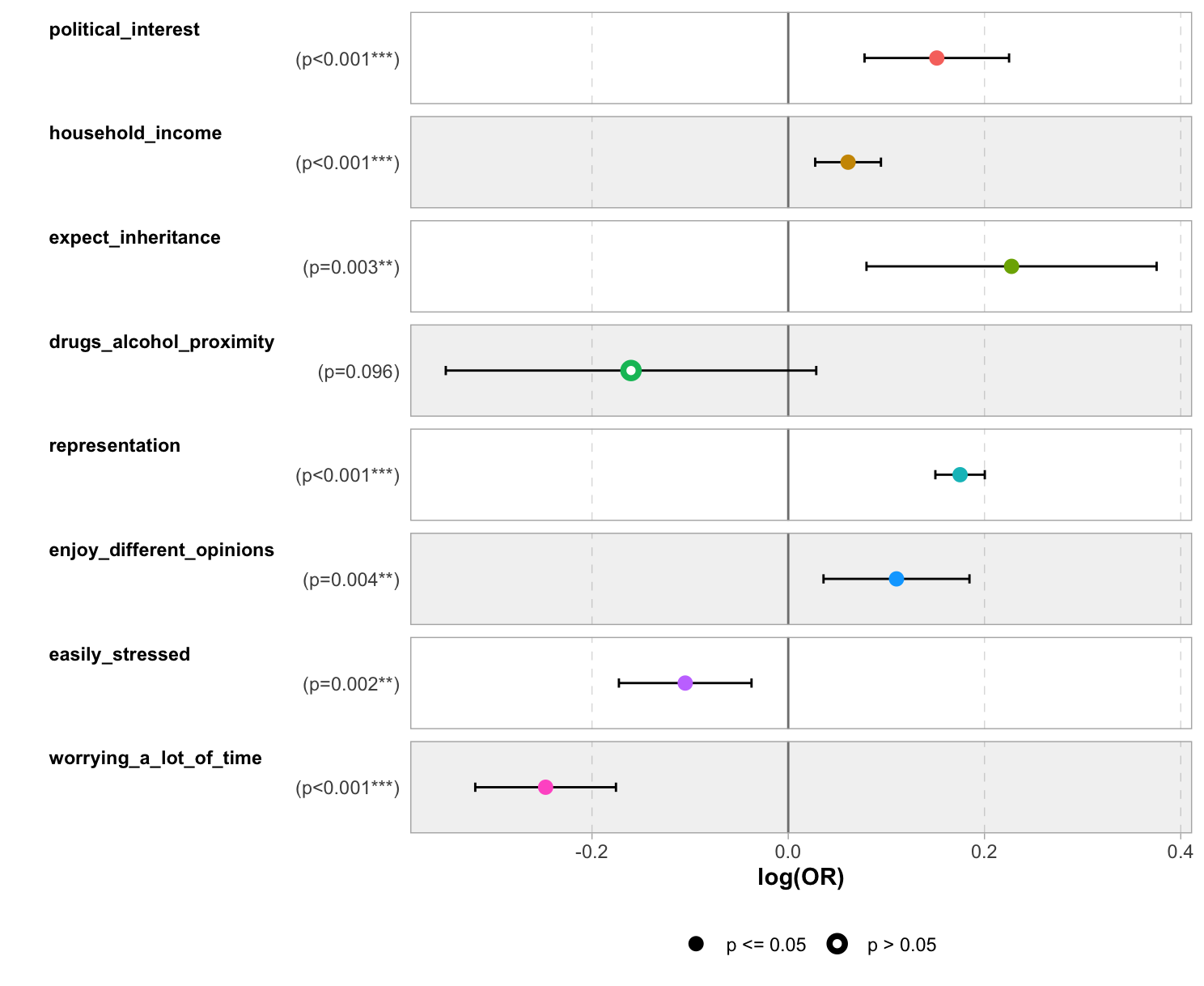

For those of you who don’t want to read a coefficient plot, certain things turn out to be good…

- Money (tends to) buy happiness, and don’t let anybody ever tell you otherwise. Inheritance also pops out as a key factor – see historian Eliza Filby’s work on inheritocracy. The growth campaigners are right to have taken control of the UK political agenda

- Tackle alcoholism and drug abuse in families. This seems to have disappeared off the political agenda despite the great work from think-tanks like the CSJ.

- Cultural inclusion is good (a proxy we have used is representation in film and media).

- Increased social contact among people is good.

- Freedom of speech is good and contact between those who have different perspectives.

- Most controversially, fixing generational anxiety is a national priority: Either through the reduction in moral progressive frameworks (Jonathan Haidt’s work suggests that modern progressive thinking is reverse cognitive behavioural therapy) or increase provisions for anxiety and counter things which cause it. I’d say the left and right both have a point here

- Democratic participation is good.

- Marriage is good (a strong correlate of other features so not in the final regression, but see the main analysis later on)

- Home ownership is good (a strong correlate of other features so not in the final regression, but see the main analysis later on)

Below is the main exhibit of this blog.

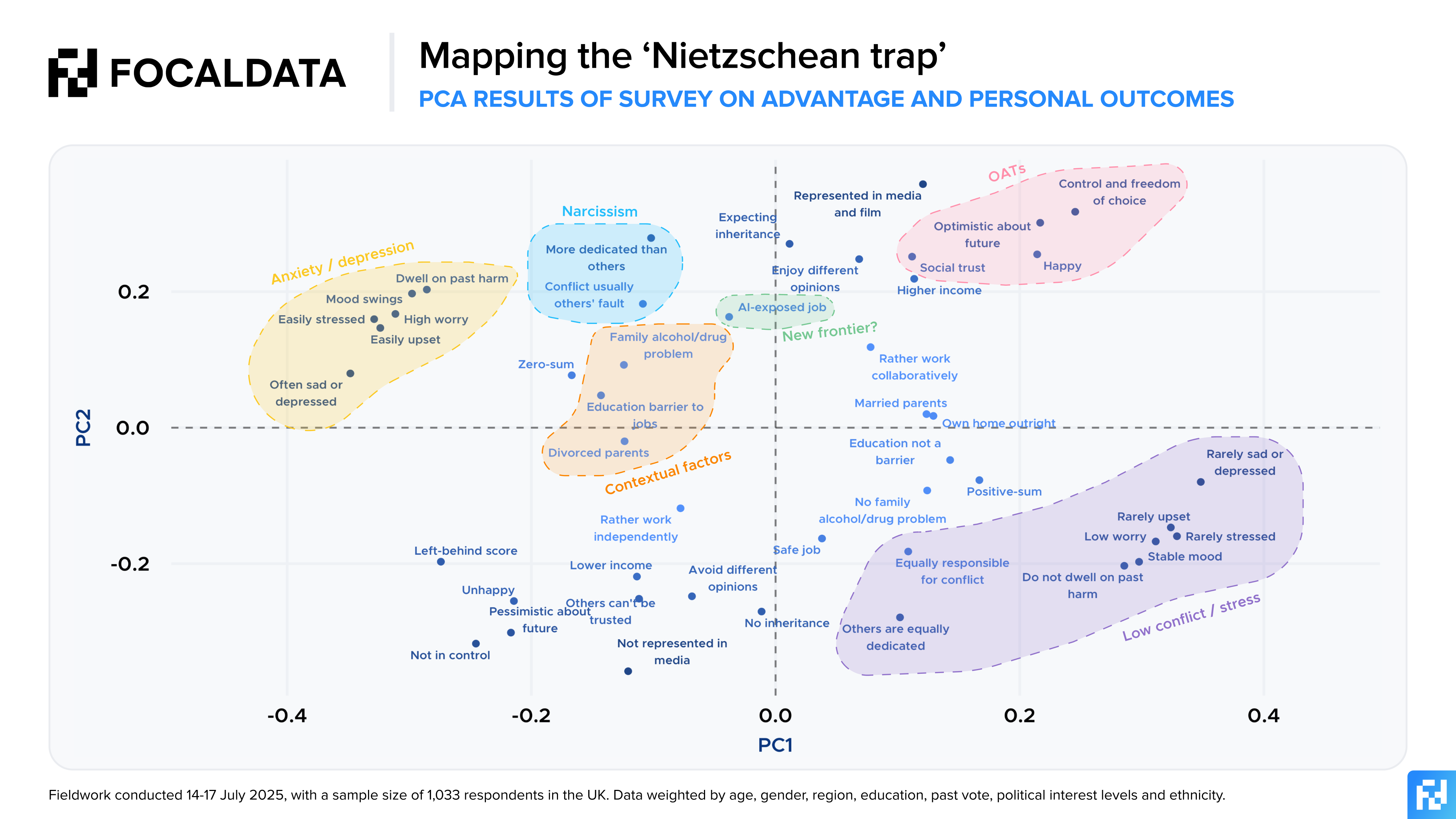

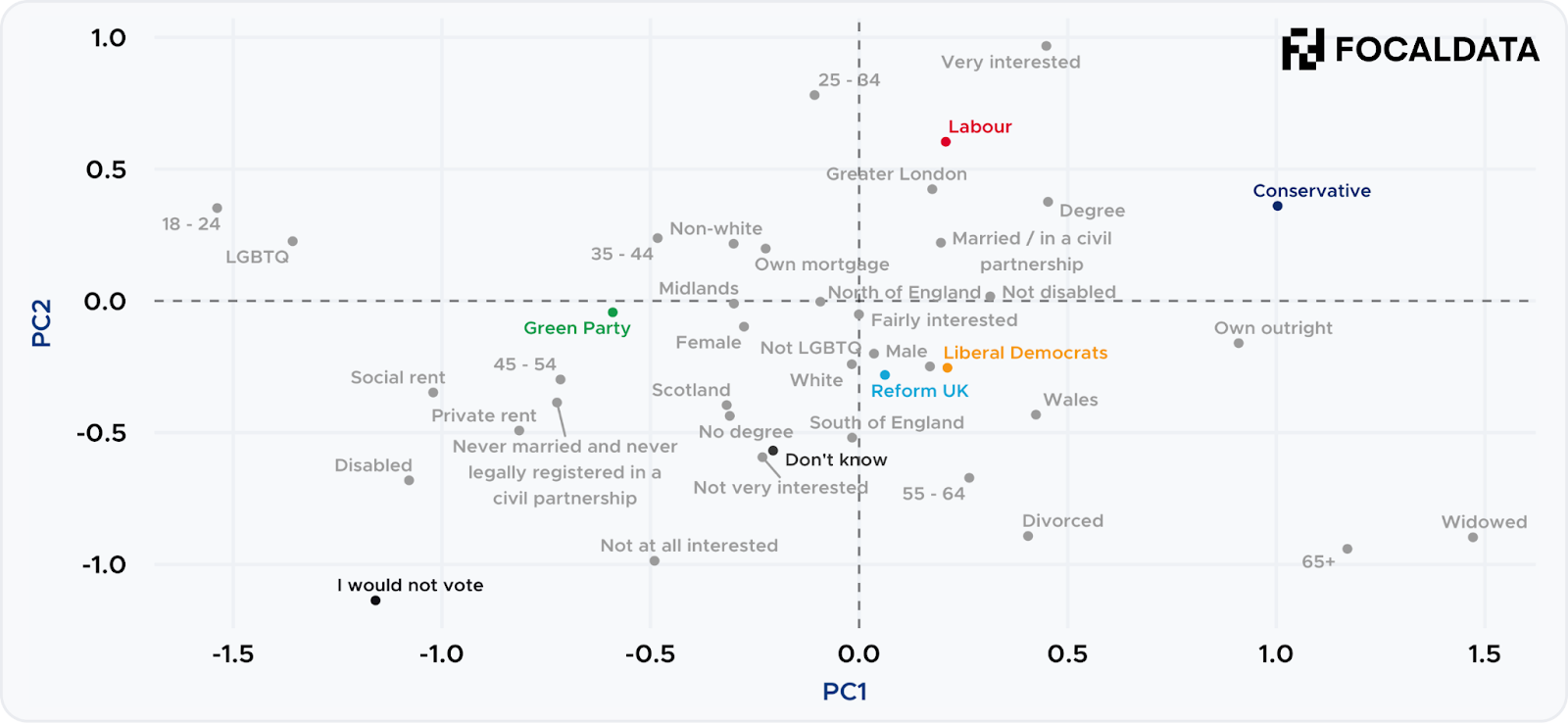

It shows how all the attributes of ideologies, agency, optimism, trust, demographics and voting intention all map against each other using a Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The closer the points are to each other, the more they covary. In the top right we have our ‘OATs’ section of the public – optimistic, happy, in control, high trust. The idea that people are in control of their lives, have choice, are optimistic, happy, and trust others are all belief sets that walk in lockstep with each other. You can see that the ‘left-behind’ score sits completely opposite this section. The different arcs of grievance are incredibly clear once you look at the data this way.

The first axis (PC1, from left to right) captures distress versus emotional and psychological stability. The strongest influences (known as ‘loadings’ in PCA language) on this axis are the level of negative thought patterns a person experiences like feeling sad and depressed, worrying a lot about different things, or dwelling on perceived harm done to them by other people. Those who have a lot of these thoughts are positioned on the left of the chart.

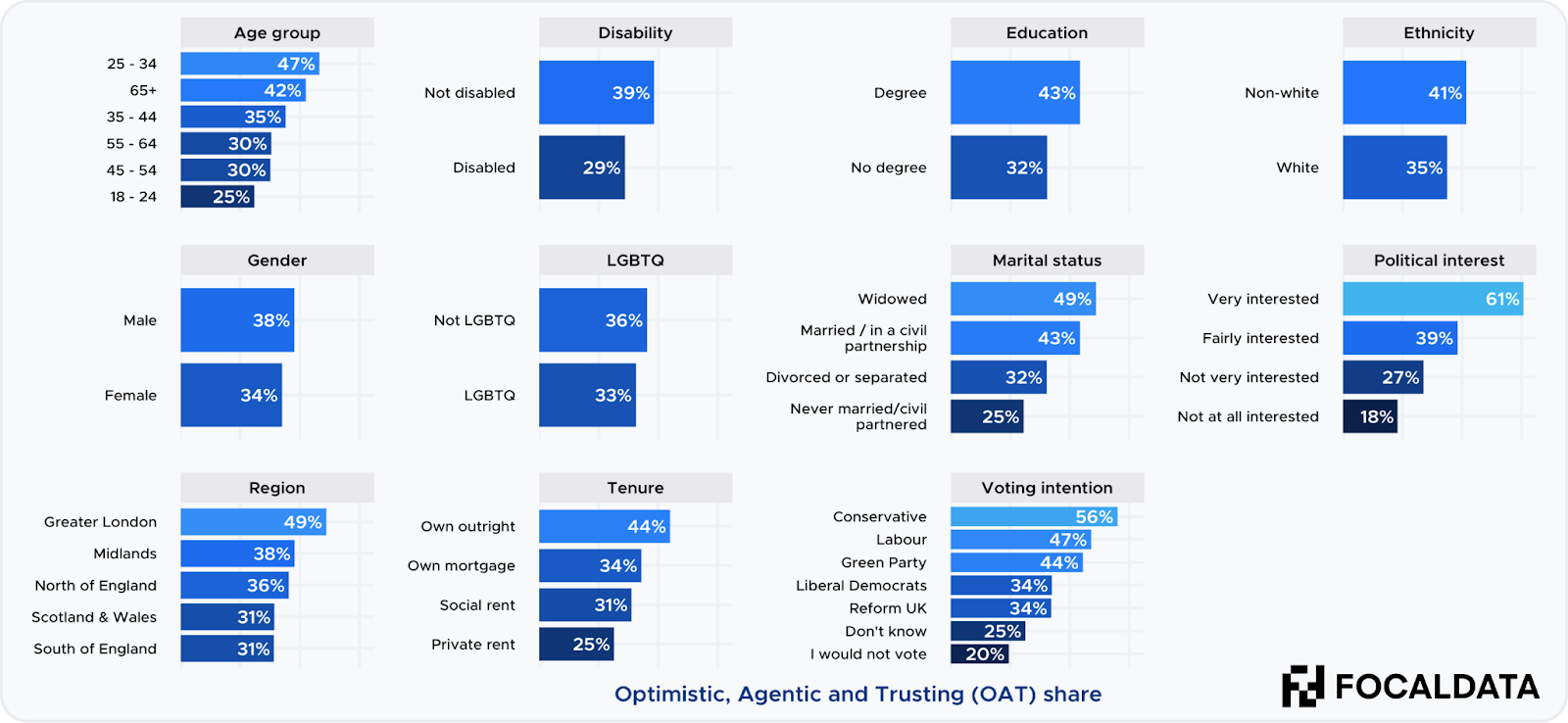

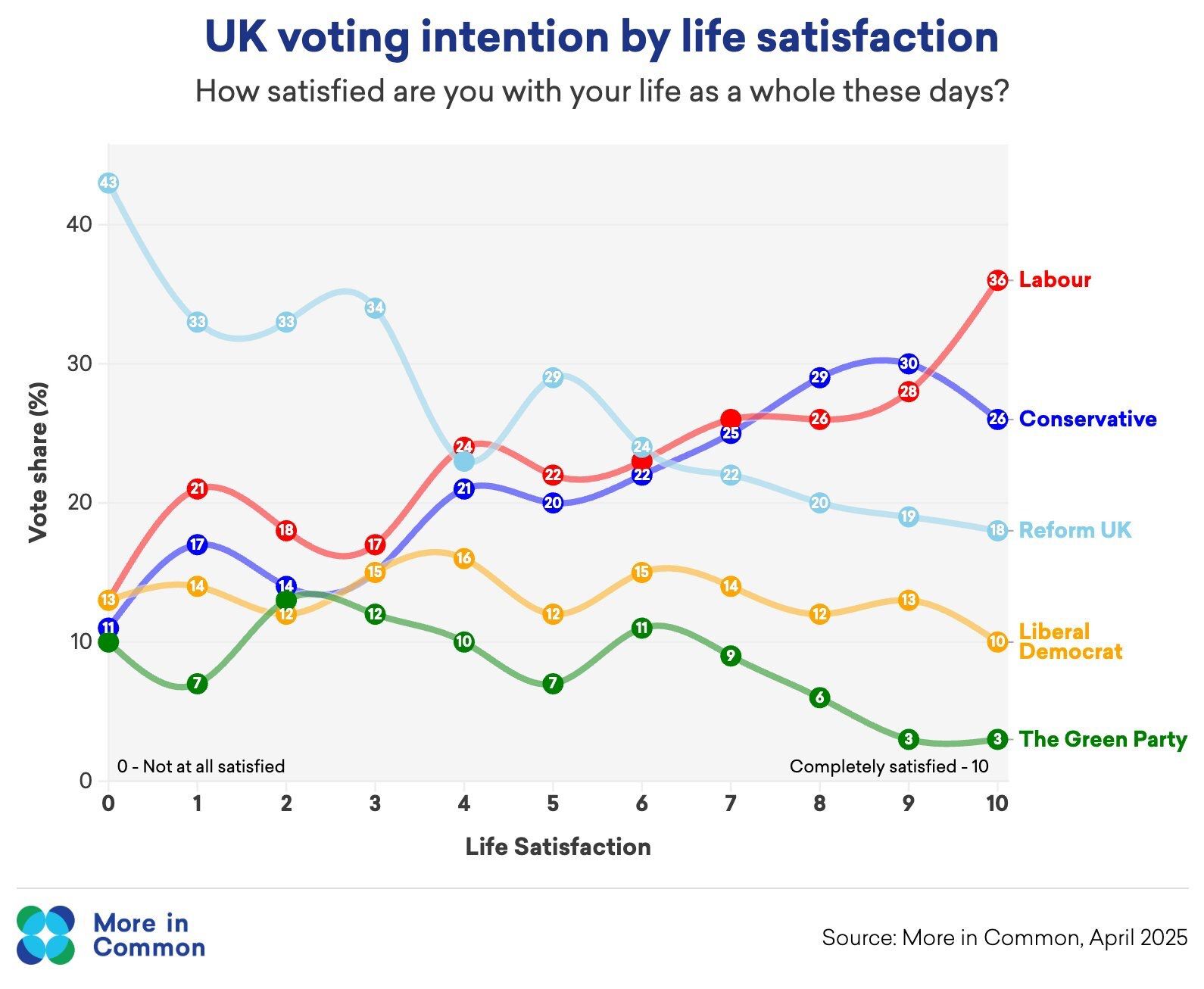

The second axis (PC2, from top to bottom) is slightly harder to pin down, but broadly centers around representation and optimism, alongside what we might simply call cognitive activity. The biggest influences on this axis are how well-represented people feel in media and film, their optimism about the future, and how much control they feel over their lives. The level of cognitive activity seemingly also has an impact – you can see high anxiety and rumination scoring positively here, suggesting this axis encompasses the sheer amount of cognitive activity someone has, regardless of its content. This dynamic goes some way to explaining why our second axis is heavily correlated with age, peaking at 25-34 before declining for each increasing age group. When we map on demographic variables, we can see that Labour and Conservative voters are more likely to fall into the optimistic, agentic and trusting (OAT) quadrant. A low combined vote share for the two parties is a symptom of an unhappy country. We find ourselves with a new political axis, one centred around happiness, trust and optimism – embodied more by the old parties – with the insurgent parties fishing in the pool of discontent and feelings of being ‘left behind’. Likewise, we also see non-voters and those who are ‘not at all interested’ in politics clearly overlapping with the unhappy, pessimistic and low-agency quadrant. Low voter turnout should be a warning sign.

Of the five major parties, Reform has the smallest proportion of OATs in its electorate, but the Liberal Democrat figures were rather surprising, too (though perhaps not worth reading into too much given the relatively small sample size of this subgroup).

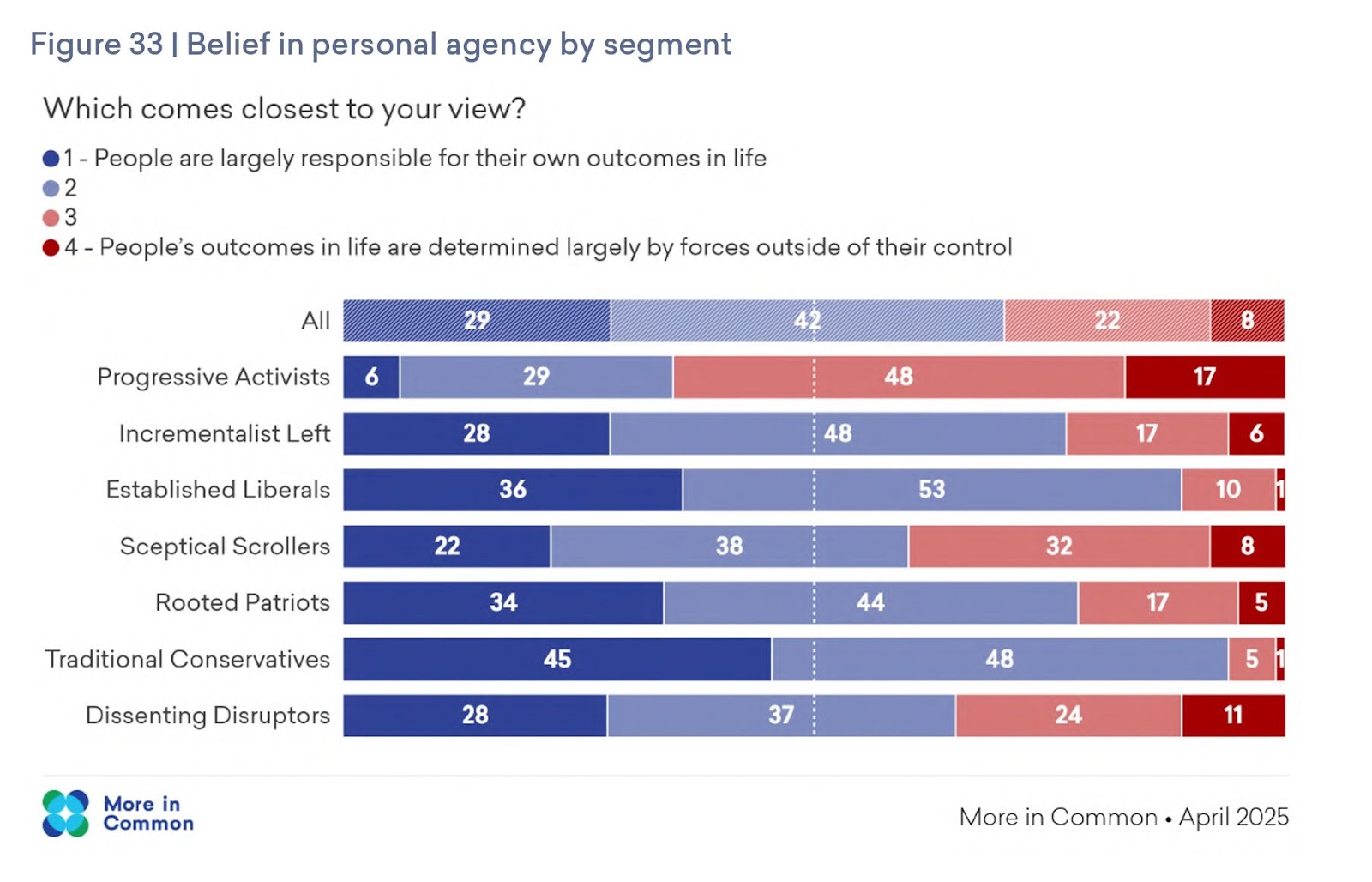

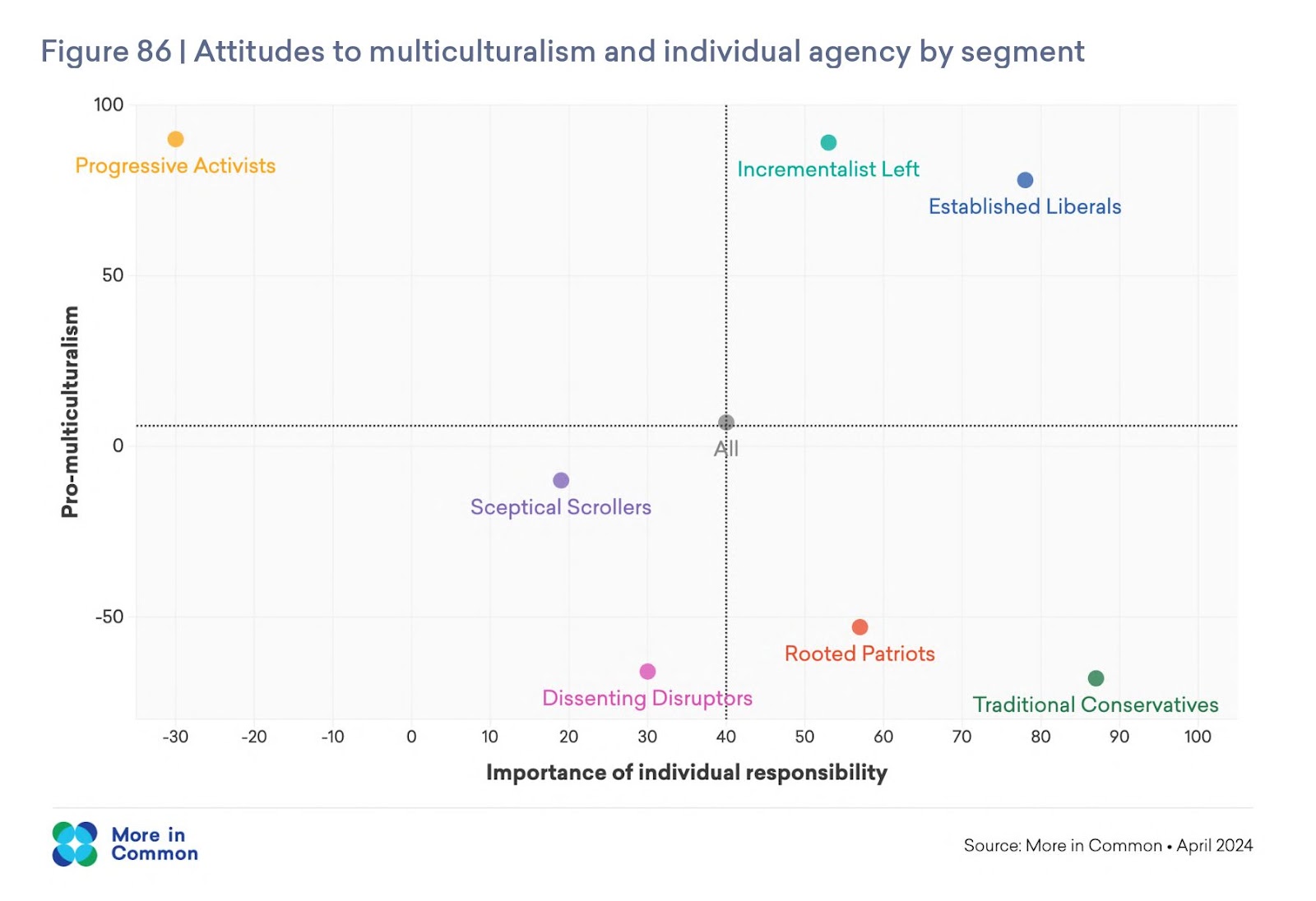

We found our friends at More in Common have alighted on a very similar set of instincts – that we are moving from one phase of politics that is fought around an axis of identity, immigration, crime, multiculturalism, back onto a multidimensional battle where agency is also incredibly important.

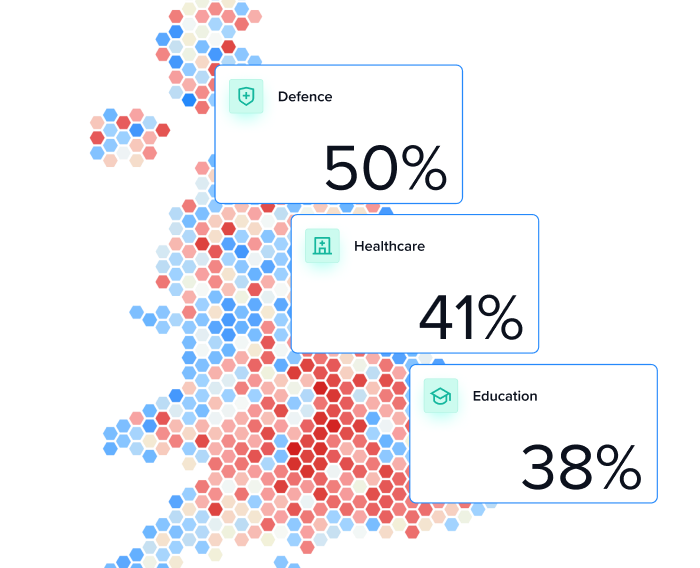

I would go a step further than MIC and make the value judgment that agency-suppressing beliefs have been positively harmful for the UK, and are the source code behind our current malaise. If you were writing a manifesto to increase the amount of agency in the country what would it look like? Radical devolution so people can actually gain control over their physical environment? Smash crime (the ultimate agency-robbing moment is getting actually robbed)? Massive civil service reform so that the UK government itself has agency to create change? Welfare reform? Challenging the use of JRs that can block progress? Deep planning reform? Public service reform to allow more choice? War on deep poverty and better state intervention into families that have multiple needs? Better incentives for married couples in the tax system? Some kind of political reform to get people invested in the political process again (incidentally the next blog is on PR: why I think this debate is coming, and why I think it’s a bad idea).

Many of the movements on the left and right which have momentum are those basically campaigning for agency. I think we’re about to enter a period in praise and cultivation of agency.

Appendix

- Left-behind score definitions:

- Not expecting to receive inheritance: Those answering No to “Do you expect to receive any significant inheritance or financial assets from your parents or family in the future?”

- Lower income: Total household income after taxes and housing costs < £2,750 per month

- Education has been a barrier to jobs: “Have you ever not applied for a job because it required a higher level of education than you have?”

- Not represented in media/film: Those answering <= 4 to “On a scale of 0-10, how well do you feel that people like you (in terms of your background or identity) are represented in mainstream media and film?”

- Unhappy: Those answering <= 4 to “Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday? Please answer on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means 'Very unhappy' and 10 means 'Very happy'”

- Disabled: “Do you consider yourself to have a disability or long-term health condition?”

- AI-exposed job: Those answering Very likely or Fairly likely to “How likely do you think it is that your current job will become fully automated (i.e. performed by machines or AI) within your lifetime?”

- Divorced parents: “Before the age of 18, were your parents ever separated or divorced?”

- Protected characteristic: “Do you identify as LGBTQ+ (e.g. gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender)?” and/or ethnic group other than White

- Low control over life: Those answering <= 4 to “On a scale of 0 to 10, how much freedom of choice and control do you feel you have over the way your life turns out? (0: No control at all / 10: A great deal of control)”

- Proximity to drug/alcohol problem in childhood: “During your childhood, did you ever live with anyone who had a serious alcohol or drug problem?”

Previous doomery trends my firm and I have written about over the past couple of years:

- The tendency of the political left to issue-bundle different causes together (Black Lives Matter, Climate, Overseas Development Aid) to create some omni-campaign that comes across as weird, unfocussed and generally reduces support for all of the above causes

- Growth of sectarian voting in Britain (before the 2024 election)

- The growth of political instability and why this may lead to massive parliamentary majorities collapsing (before the 2024 election)

- The fusion of social issues with economic issues to create a new issue space around job access and job equality that will create incredibly emotive and sharp divisions in Britain

- Observing the US Democratic party as a guest of theirs at their conference last year before the election and being absolutely horrified by donor-led policies

- The decline of social capital and friendship intensity in the US and UK

- The growth of zero-sum thinking reducing our ability to co-operate

This piece was originally published on my Substack newsletter, 'The Political Whiteboard'. Check it out here.

If you or anyone you know regularly run polling, we'd be happy to run a free couple of questions for you -- we'd love to demonstrate the speed of our platform and showcase the technical capacity of our research team.